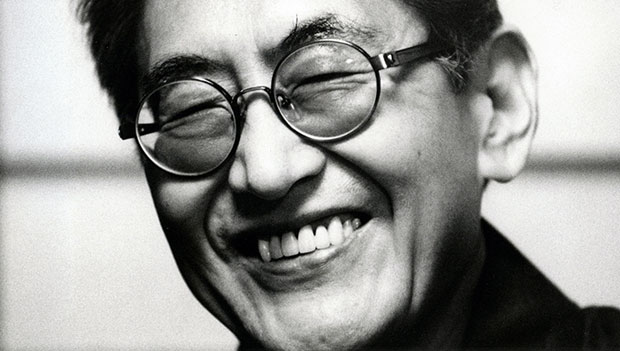

Enemy of the status quo Nagisa Oshima, director of the 1976 lightning-rod film In the Realm of the Senses, died Tuesday afternoon at a hospital near Tokyo. The Japanese filmmaker’s company Oshima Productions confirmed to the AP that he succumbed to a battle with pneumonia, after spending years recovering from a devastating stroke in 1996. He was 80.

Oshima was the director who dragged Japanese cinema kicking and screaming into the modern world. Born in 1932, he came of age in a postwar Japan that was shattered financially, economically, and culturally, and left uncertain how to face the future. While the island nation’s director best known in the West, Akira Kurosawa, looked to the past to find sorely needed virtues of honesty and decency in his period samurai films, Oshima, younger by about 20 years, instigated a complete generational break. Horrified by the militarism and class injustice that had plunged his country into war, he would become a student radical, and then, as a filmmaker, would focus on the problems of contemporary Japan and on the young people who would eventually become its caretakers. Not that they were steady caretakers, by any means. In fact, the title of his second feature, Cruel Story of Youth, could sum up the way he’d often present the post-war generation. His camera lens considered all sorts of outcasts and underdogs: gays, the politically marginalized, prisoners of war, people affected by racism, convicts on death row. His objective: to shatter Japan’s remaining taboos.

And was that objective ever accomplished with his best-known film, 1976’s In the Realm of the Senses. This shocking investigation of a murder case in pre-World War II Japan was among the first non-pornographic films to receive mainstream distribution (in Japan, and, really, anywhere) despite featuring unsimulated sex sex scenes. Oshima even had to have the film negatives developed in France so as to circumvent Japan’s strict anti-pornography laws at the time. The resulting indecency debate very much mirrored similar discourses over the inflammatory sex and violence in other ’70s movies like Caligula, Last Tango in Paris, and Salo! Or the 120 Days of Sodom. Not surprisingly, it raised Oshima’s profile in the West like never before, and two years later he won the Best Director honor at the Cannes International Film Festival for his In the Realm of the Senses follow-up, the ghost story Empire of Passion.

If we can call the more modern, socially-engaged, politically-demanding Japanese films of the ’60s and a ’70s a “New Wave,” it’s largely thanks to Oshima’s work. It’s fitting that his first feature, A Town of Love and Hope, was released in 1959, the same year that the French New Wave kicked off with Francois Truffaut‘s The 400 Blows and Alain Resnais‘ Hiroshima Mon Amour, because, like those New Wave mavericks in France, Oshima was committed to redrawing the cinematic map. After his 1960 film Night and Fog in Japan was pulled from distribution for fear it would inspire political upheaval, Oshima left the stodgy Shochiku studios, the long-time home of Japan’s greatest classical filmmaker Yasujiro Ozu, and embarked upon a career as an independent filmmaker by founding his own company. In the Realm of the Senses may have been the culmination of his experimentation, but he first broke barriers in the depiction of racism with The Catch (1961) about an African American prisoner of war held in Japan during World War II, Violence at Noon (1966), which detonated classical cinematic form with its more than 2,000 cuts, sexual taboo-buster Sing a Song of Sex (1967), and his blistering screed against capital punishment Death by Hanging (1969). Rapists, gangsters, murderers, sexual deviants—they’re all represented at one time or another in Oshima’s work.

After his international breakthrough in the ’70s, Oshima directed one of his most popular features, 1983’s Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, starring David Bowie as a prisoner of war in a Japanese internment camp. Even after his stroke in 1996, Oshima continued working and directed one last feature, Taboo, about gay samurai in medieval Japan starring comedian-director Takeshi Kitano. In its own way, Taboo did for the samurai film in Japan what Brokeback Mountain did for the Western in the U.S. It proved that he’d never lost his commitment to breaking barriers and had always maintained true to the self-styled mantra he uttered during a court hearing over the alleged indecency of In the Realm of the Senses in 1976: “Nothing that is expressed is obscene. What is obscene is what is hidden.” For Oshima, we can safely say his mission was accomplished.

Follow Christian Blauvelt on Twitter @Ctblauvelt

[Photo Credit: The Asahi Shimbun/Getty Images]

Craziest Celebrity Swimsuits (Celebuzz)