Francis Ford Coppola, Part I

Where do artists get their ideas? Seriously. Do ideas spring up while facing the white page? Are they random notions that appear without warning while looking for a new broom at Target? Are they inspired by that last fight with a spouse, or the way one’s grandmother stared at her husband’s empty easy chair? Well, I’m a writer, and I can tell you that it’s hard to parse, because it’s all of the above, and more. The people who write novels and make movies don’t understand where their ideas come from any better than anyone else.

Where do artists get their ideas? Seriously. Do ideas spring up while facing the white page? Are they random notions that appear without warning while looking for a new broom at Target? Are they inspired by that last fight with a spouse, or the way one’s grandmother stared at her husband’s empty easy chair? Well, I’m a writer, and I can tell you that it’s hard to parse, because it’s all of the above, and more. The people who write novels and make movies don’t understand where their ideas come from any better than anyone else.

On the other hand, there’s this notion, popular until the annihilating effect of postmodernism rendered interpretation silly, that in a sense every artist of worth only has one idea, rendered over and over and over again in finer and finer relief. And if that artist has restlessness in her soul, like most artists do, that idea gets refined, developed, riffed on, remixed and rewritten so that it remains fresh throughout a career and throughout a lifetime. Because in a sense, artists are always making a kind of self-portrait.

With this in mind, I thought it might be neat to work our way through the work of some classic Hollywood directors. The big guns, the ones you remember, the ones whose work is indistinguishable from that of others in the history of film.

Who better to start with than a director who changed everything in the 1970s, disappeared for a decade, and has recently returned in a humbler form? Francis Ford Coppola, director of this week’s classic Hollywood movie:

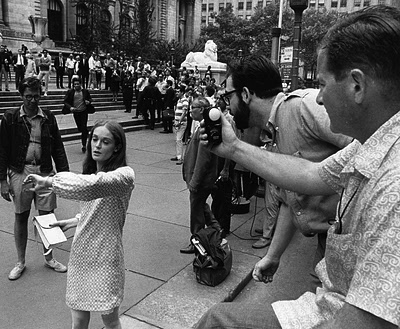

1966’s You’re a Big Boy Now.

The man who would direct The Godfather, the most popular, influential, and critically acclaimed movie of his generation, started in a somewhat silly, very 1960s way, with a countercultural coming-of-age movie that was all about sex, drugs and the Lovin’ Spoonful. Only the lack of a guy in a gorilla suit keeps You’re a Big Boy Now from being a perfect ’60s freakfest. In Coppola’s defense, these were the times in which he was living.

Like the rest of the country, the Hollywood movie machine had by the mid-’60s found itself in a cultural and financial blind alley. The breakdown of the studio-system monopoly and the rise of television contributed to the radical drop of box office, but the real problem stemmed from Hollywood’s inability to figure out just what floated the boat of young America. Then, like now, it’s the young who fork over the most when it comes to entertainment.

Out of desperation, Hollywood turned to gigantic productions and desperate technological measures: widescreen, 3D, monumental special effects. Sound familiar?

Out of desperation, Hollywood turned to gigantic productions and desperate technological measures: widescreen, 3D, monumental special effects. Sound familiar?

At a loss, Hollywood turned to B-movie virtuosos like Roger Corman, who could make movies for next to nothing. Corman pointed the studios to the film-school-trained group of cinephiles he’d been hiring to shoot schlocky horror films, Francis Ford Coppola among them.

Coppola directed Dementia 13 for Corman, and that is, technically, his first feature film. But Coppola wanted something different than B-movie psychosexual slashfests. When he got distribution through Warner Bros. for his UCLA thesis project, You’re a Big Boy Now, he had finally arrived. Lauded by the committee at Cannes and film critics all over the world, You’re a Big Boy Now is the first genuine piece in the Francis Ford Coppola’s body of work.

The movie’s insane; there’s no other way to say it. It’s also a perfect movie for its time. The story’s about a boy from a well-to-do ’50s-style family that attempts to push him past his arrested development by forcing him to live by himself in the big city. The advice of his mother is wonderfully contradictory, and a perfectly ironic indictment by the children of the ’60s and of the families of the ’50s: “Don’t eat too much, don’t stay out too late, don’t go to suspicious places to play cards, and stay away from girls. But most of all, Bernard, try to be happy.” She wants him to be happy, as long as he fits within the social mores accepted by his parents. As you can imagine, that doesn’t work out so well.

The boy falls in with ne’er do wells that include a roving Beat poet of sorts, who advises the boy to find a girl who’s “willing,” taking him out to fly a kite, offering lines from his body of work: “Oh don’t you think it’s very odd / That we should kneel and pray to God / When by all accounts we might / Send our problems up by kite!”

But the story’s only half of it. Coppola uses found footage, intercuts, in-camera effects, out-of-focus composition, musical interludes, and radical redubbing to create what must have been a startling effect in 1966. These effects only occur from the perspective of the boy, bringing us inside his subjective journey in a jarring and visceral way. All told, the movie heralds the arrival of the American counterculture with a whimsical but definitive bang.

Coppola began his film career with an iconoclastic comedy, a coming-of-age story that pits the stolid mores of the ’50s against the sex and drugs and rock-‘n’-roll of the counterculture and won him accolades from film critics worldwide. But it’s hard to remain a force for the counterculture once you’ve been accepted by the establishment.

What did Coppola do next? Find out next week.