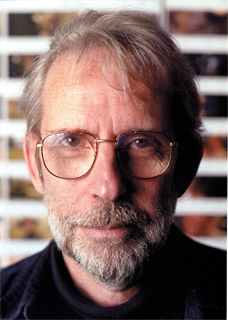

One of the secrets to the success of Francis Ford Coppola is the legendary sound and film editor Walter Murch. Murch did the sound and/or film editing on all of The Godfather movies, American Graffiti, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, Jarhead and The English Patient, to name just a few. He’s the only person to be nominated for an Oscar for editing different films using four different editing systems, the first person to win an Oscar for editing with a digital system, and the only person to win two Oscars on one film for both sound mixing and film editing.

One of the secrets to the success of Francis Ford Coppola is the legendary sound and film editor Walter Murch. Murch did the sound and/or film editing on all of The Godfather movies, American Graffiti, The Conversation, Apocalypse Now, Jarhead and The English Patient, to name just a few. He’s the only person to be nominated for an Oscar for editing different films using four different editing systems, the first person to win an Oscar for editing with a digital system, and the only person to win two Oscars on one film for both sound mixing and film editing.

He’s a rock star, and when he’s rocking the hardest, nobody notices his work. Here’s an example:

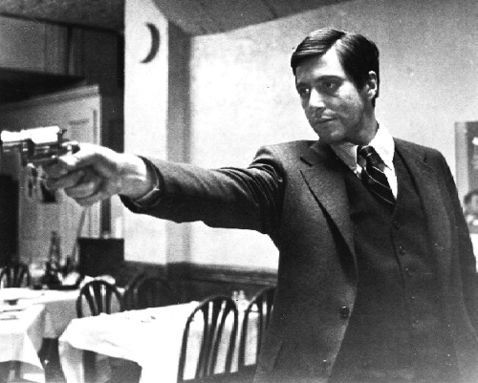

In the famous sequence in The Godfather where Michael kills Sollozzo and McKlusky, Francis Ford Coppola wanted no sound at all. In any other Hollywood movie of the time (or this time) that sequence would be the time for super suspenseful music to jack up the audience. Coppola wanted to open up a sonic void in which the audience would squirm just as much as Michael. Murch agreed with the bold decision, but when he played the scene without sound it just didn’t feel right.

In his book about editing, In the Blink of an Eye, Murch makes a list of the six most important factors when making editing a film. Things like ‘continuity of space’ and ‘tracing the viewer’s eye movement’, usually considered the most essential parts of editing, don’t even make it into the top three. At the top is ’emotion.’ According to Walter Murch, the most important factor in whether or not to keep a cut is the degree to which it gets the audience feeling the way the film needs to make the audience to feel.

Following that principle, Murch did something absurd. When Michael goes into the bathroom to get the gun, Murch mixed in the sound of an elevated train. Not only are there no visual references to an elevated train anywhere near the restaurant, the volume of the rumble is way too loud for what one might hear in the bathroom. It makes no logical sense. What the sound does, however, is emphasize the silence that precedes and follows it. Murch repeats this sound trick decades later in Sam Mendes’ Iraq war movie Jarhead, when the silence following the explosion of a mortar shell is set off by the delicate sound of falling sand.

Murch has that kind of touch.

Here’s another story from The Godfather:

Coppola hired Nino Rota to compose the score that would become iconic in film history. Rota had scored films by folks like Frederico Fellini, Luchino Visconti, and Franco Zeffereli – the man was high cinema royalty in Italy and around the world. Naturally when our old friend Robert Evans heard the score mixed over an early cut of the movie, and hated it. He’d heard Italian composer and expected something like the American Henry Mancini, who composed the Pink Panther theme and won an Academy Award for “Moon River” from Breakfast at Tiffany’s. A brilliant composer, to be sure, but an ocean away from the deeply classical and fully ethnic work of Nino Rota.

Coppola left Murch to deal with the situation. Murch, true to his character, let Evans talk it all out until he got to one specific sticking point: in the scene where studio head Jack Woltz discovers the head of his prize racehorse in his bed, Rota, at Coppola’s suggestion, had scored a beautiful waltz. Evans thought this was just too much.

So what did Murch do?

So what did Murch do?

Murch ordered a second recording of Rota’s score. Then he played the two tracks just out of sync, tracking the A track over the B track in the ABA structure of the waltz, creating a beautiful, haunting effect Rota had never intended. Go back and watch that scene again, but close your eyes and just listen to it. When you really hear the melodies scraping up against one another, you can get an appreciation for the strange brilliance of Murch’s choice, and the way that it aids in creating the tension and horror of the scene.

That’s the kind of thing Walter Murch brought to all of Coppola’s early films. Without Murch, there is no Coppola. You’ll hear more about Murch as we move through The Conversation and a whole lot more when we get to Apocalypse Now, a movie that Murch contributed so much to they had to invent the title “Sound Designer” just to wrap their heads around his accomplishment.

If you’re curious about the art of editing and the fascinating brain of Walter Murch, check out a book called The Conversations: Walter Murch and the Art of Editing Film, in which novelist Michael Ondaatje talks with Murch about his work.

Next week we return to a trip through the work of Francis Ford Coppola with The Conversation, wherein we will meet a very, very young Harrison Ford.