I’m old enough that when I first saw Apocalypse Now, I saw it at a friend’s place on VHS. It’s such a long movie that it came in two tapes, and somehow stopping the movie, popping out the tape, going to the bathroom, taking a walk — it all brought you out of Francis Ford Coppola’s vision.

I’m old enough that when I first saw Apocalypse Now, I saw it at a friend’s place on VHS. It’s such a long movie that it came in two tapes, and somehow stopping the movie, popping out the tape, going to the bathroom, taking a walk — it all brought you out of Francis Ford Coppola’s vision.

When I heard the film would be playing at Golden Gate Theater, I went all by myself. Well, there were eight other people in the theater. All there alone. Every single one of us sat through the credits, and when the lights came up we sat there still, overwhelmed, stuck. It’s that feeling when you’ve been through something so wrenching you know any move you make might completely shatter your armor, laying you bare for all to see. After what felt like a few minutes we stood, looked each other in the eye one by one, and filed out of the theater. This actually happened. I really wish someone had been there to tell us that what we should do next is watch Gardens of Stone.

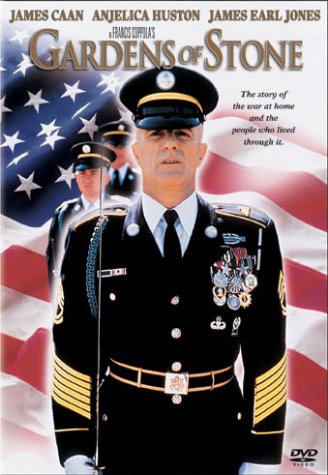

Gardens of Stone sits in the center of what I’m going to call Francis Ford Coppola’s nostalgia period, which begins with The Outsiders and ends with the operatic whimper of The Godfather Part III. Each of these movies casts its eye backwards in some way, like a man in a state of decay trying to understand what went on when he was young.

I’m more and more convinced that Coppola’s movies don’t decline in quality so much as shift focus. The vitality and immediacy of Coppola’s early period have fallen off, giving way to a more somber turn of mind. Gardens of Stone perfectly fits this posture of reflection. I’ve talked before about the way Apocalypse Now subverts most war movies by avoiding any easy answers. Most war movies are either jingoistic yawps to the heart of the country or parables of humanism. Either way, they break down to an easy moral dualism, and if anything kills great art, it’s easy moral dualism.

Apocalypse Now eschews morality and aims instead at a kind of ritualistic narrative that evokes the part of mankind that needs war and death and blood without ever once turning its head away from the consequences. War is a force that gives life meaning, you might say. Coppola doesn’t let you escape. He’s interested in truth, aesthetics, and the human psyche, not moralizing. Which is why, I think, the understated Gardens of Stone did so poorly: it provides a kind of closure for baby boomer Vietnam anxiety.

Apocalypse Now eschews morality and aims instead at a kind of ritualistic narrative that evokes the part of mankind that needs war and death and blood without ever once turning its head away from the consequences. War is a force that gives life meaning, you might say. Coppola doesn’t let you escape. He’s interested in truth, aesthetics, and the human psyche, not moralizing. Which is why, I think, the understated Gardens of Stone did so poorly: it provides a kind of closure for baby boomer Vietnam anxiety.

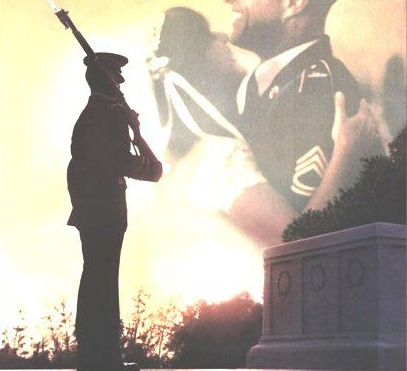

The story focuses on Sgt. Hazard, assigned to the Old Guard in Fort Meyer, Virginia, which provides funerals for fallen soldier whose tombstones constitute the gardens of stone in the title. Hazard’s ambiguous feelings about Vietnam form the center of a bunch of characters who all have different feelings about the war. Some hate it, some love it, and some want to go fight in it. Most other filmmakers of his generation would put us in the mind of a protagonist that had clear feelings about war, or at least come to a clear resolution. Coppola is not so forgiving. Hazard begins the movie cautioning the young soldier Willow, played by D.B. Sweeney, against going to Vietnam, but Hazard doesn’t make it through the whole film without passing through his own moral ambiguity. All the while, Hazard and Willow are surrounded by the unambiguous consequence of all war: death.

The movie is steeped in the kind of death that comes home from war — a death without the sound of gunshots or the spray of blood; a death transformed by governmental landscape gardening into a kind of sanitary beauty; a death that, often, must be personal to cause lasting and serious change.