While the bulk of attention this season has been attached to movies like Lincoln, Argo, and Zero Dark Thirty, there is another Academy Awards nominee that deserves the public’s focus: How to Survive a Plague, filmmaker David France’s challenging documentary about the heat of the AIDS epidemic in the late 1980s and the rise of organizations devoted to combatting the outbreak. France, who lived through the tumultuous era, joining the forces of activist groups like ACT UP and individuals like Peter Staley and Larry Kramer, and has returned to the era with his 2012 doc, which looks to applaud the efforts of the individuals who founded the fight against the virus, and to call the present generation to carry forth in the fight.

Just to start things off, I’m interested in knowing your personal attachment to the history of the disease, and what brought you on to tackle this project to begin with.

David France: I moved to New York from the Midwest, from Michigan, in 1981. As part of my coming out. Back then, you had to move to New York or San Francisco if you wanted to live openly as a gay person. Which is not that long ago. It’s really kind of surprising how far we’ve come since then.

But I got to New York right before — just weeks before the first public report of HIV. And they weren’t just reports. My friends were getting sick. We were all confident that it would get us, whatever it was. We were all trying to find a way to survive. And it was very personal. For me, my activism — as it was, a kind of activism — was to become a journalist. And I was studying philosophy at the time for my PhD, and just sort of trying to find information to publish about AIDS. Anything. Even before it was called AIDS, I was writing about it. So to me, it was very personal. And by 1987, when AIDS activism took the form of ACT UP — and that’s when How to Survive a Plague opens up, in 1987 — I had lost many friends, including the person I moved to New York with from Michigan, who had died of the disease. And my boyfriend was HIV positive.

It was all part of the war. And I was kind of the war correspondent, with the job I did. And I hoped that somehow, ACT UP would succeed. That somehow it would find the answer, or cause the answer to be found by others in time to save our lives. So that’s what my investment was. I was the first person to write about ACT UP. And I was covering AIDS from a science perspective, [and] I gravitated to the specific individuals whose stories I tell in How to Survive a Plague. I watched them, I rooted for them. When they reported from their meetings with the pharmaceutical industry leaders at the ACT UP meetings on Monday nights, I took notes, I learned from them what was happening in the area of science, and that informed my journalism around the science. So, I knew the story. I knew what they had accomplished and were accomplishing. And fortunately, they did bring up, at this time, a solution to HIV. But unfortunately, not in time to save everybody, not in time to save my boyfriend’s life. And he died in ’92. It’s to him that I’ve dedicated the film.

RELATED: The Documentaries of Sundance 2013 That You Absolutely Must See

Since there have been the efforts of ACT UP, which you chronicle in the film, and various other projects that have been undertaken over time to spread awareness and institute change, what specifically did you want to accomplish with How to Survive a Plague that you didn’t think had already been accomplished successfully?

DF: Actually, I think that’s a really big thing. Of all the ways that the story of AIDS has been told in the past, we’ve always focused on the first three or four or five years of the epidemic, which means that the story had been about a mysterious new ailment impacting a relatively hidden and disenfranchised community, and all the tragedy that surrounded that. And that’s really the story of And the Band Played On, that’s the story of Larry Kramer’s play The Normal Heart, Angels in America. And nobody had gone back and tried to tell the story not of what HIV did to a community, but what a community did in response. What a community did back to HIV. How the community wrestled this virus into some kind of standoff. And that’s really the story of all this incredible, revolutionary activity that was going on. ACT UP and AIDS activism, and AIDS treatment activism specifically are the last great social justices movements of the last century. And that story hadn’t been told, for some reason. That story of how this small handful of people — mostly people with AIDS — changed the way we think of gay people, changed the way medicine is practiced, changed the way science is undertaken, and pills are designed, and medicine is regulated and marketed. Changed, really, the role of the patient in the whole equation of health care. We hadn’t yet gone and given the proper round of applause to that. And that’s what I wanted to do with the film.

The movie itself, from start to finish, there’s so much tragedy that is illustrated. But at the end of the movie, there’s a little bit of an uplifting feeling when you show how so many of the individuals have gone on to successfully manage the disease, and to continue the work, and to live successful lives. I’m wondering what the ending of your movie is trying to provoke. Or you trying to influence any future behavior, or is it more of a showcase of a history, and of a people, and of the movement?

DF: My first goal, when I began working on the documentary, was to rescue this movement from being forgotten. And to embrace it and enshrine it as an essential part of modern American history. I remember watching Eyes on the Prize, that incredible documentary about the civil rights movement, when it was first made. What that documentary did for me was to instill in me the idea that that was my history, that that was our history as Americans and as human beings. It wasn’t just a story about a community trying to empower itself. We all inherited that as our legacy.

And I wanted to do the same with AIDS activism — and, really, the dawn of the modern gay movement. To say, to the generations, ‘These people created the world that you inherited. And we all owe a lot to them for that.’ So, it was really this idea that I wanted them to be canonized, was my main first goal. And I think just the idea that people embrace those historical moments as their own creates action. And we’ve seen at the ends of screenings for this film that people — especially people who don’t know anything about this history — get really inspired by it to do something meaningful and transformative, and sometimes really fun, in their own lives, by watching how this group of people facing death were able to arm themselves, not just with power, but with a sense of humor, and an incredible sense of community to bring themselves through.

So yeah, I love that it’s inspiring people. And it’s inspiring people outside of AIDS and in AIDS. It’s inspiring people on college campuses to form groups, to work on trying to make sure that these pills can get out to all the people who need them. Currently, they get out to fewer than half of the people with HIV. So how do we get them out to the rest of the world? But also in areas like climate change and reproductive rights. World hunger. Activists from those communities have been looking to this film as inspiration for strategy and for really understanding how democratic grassroots movements can work. How you can successfully impact these intractable problems and make a difference.

Just going off that a little bit, as you talk about how you can successfully carry forth with this kind of behavior, we see a variety of types of protests in the documentary. Do you have a perspective on these different types of protests — the success of certain types over that of others, or if they would be as successful today?

DF: Or if you could even do them today! In the post-9/11 world, things are different. One of my favorite scenes in the film is the response of the activists to Sen. Jesse Helms. Helms is this incredible obstacle. He takes the floor of the senate and actually cheers on the death of gay people with AIDS. You wouldn’t believe it if you didn’t see it, that that could have happened in our America. In trying to concoct response to him, they did press conferences, they did every conceivable thing to try to get around Jesse Helms. He was controlling funding. He was making sure that funding was attached to moral and religious language, which kept it from going to research for really essential things. Especially for HIV prevention.

And that protest, where they went to his house and climbed on his house and unrolled a condom — first of all, that was something that could never happen today. If you climb up onto a senator’s house today, you’re likely to be shot off by a sniper. But what they were doing there was sharp political ridicule. Through that ridicule, they were trying to turn the media and the ordinary public against this forceful, powerful man. And it worked. Or at least it began to work. Along with all the other work that they were doing. But I think we haven’t seen ridicule used effectively in that way in recent grassroots actions or political movements. Like Occupy. Occupy didn’t seem to have a sense of humor. Maybe it just didn’t have a sense of humor, but there’s a role for humor in political activism that is really powerful and really effective. They show that in that action, and in other actions in the film.

Do you think there has become any kind of substitute for that today, or do you have an idea of what one should be? Considering the different attitude people have today about the issues and about protest, what do you think would be an effective way to carry forth with this kind of movement in the present?

DF: I wonder. The first thing, I think, would be to advise people to get off of Facebook and to actually sit in a room with people. Facebook event organizing tools might get people on their feet, or might get people to sign a petition, but there’s really nothing like getting people in a room together. Or a park. Someplace to gather or discuss.

That was the power of ACT UP. You clearly see that, when they have their Monday night meetings, where they review what happened last week, and the committees report out their new findings … that sense of there being a human connection is really powerful. And you know what you also see in the footage? People were having fun. It gave them fun. It added fun to this horrible, horrible circumstance. And you also see how flirtatious those meetings were. And it became romantic, as well as political, as well as cultural, as well as a community gathering. And the alchemy of all of those things together sustained it in a very massive way. A thousand people meeting every Monday night in New York, hundreds of people meeting every Monday night in hundreds of other cities. There were, at one point, 200 and 300 and 400 ACT UP chapters around the world. All operating on the same principle, all doing amazing and often transformative work. I think [this was] made possible by their constant arrival and return to the same hub, to the same meeting place, to find more strength and sustenance. But also, to take individual ideas and have them synergized in that group space, was really amazing to watch.

I get what you’re saying — if you feel like you’re fighting for a group of people as opposed to just your own cause…

DF: Exactly. Your ideas become larger because they are filtered through and magnified by the other people who adopt them and embrace them. I’m not an activist. I’m a storyteller. A historian, a journalist. But I do think that the work that ACT UP was able to accomplish and the innovations that they brought to activism represent a kind of a new paradigm in how to affect change from the outside that has utility in all sorts of other areas.

NEXT: Oscar Nominations and the Continued Fight Against AIDS

You were talking about how it is important just to showcase these ideas and to spread the messages. Do you think that your Oscar nomination is going to help that cause?

DF: The Oscar nomination is a dream come true. The dream is — the reason that I made the film in the first place to make sure that everybody knows what happened, and who did what, and how these improbable odds were surmounted. And the nomination just gives us further jet fuel for our flight into the new generation. We saw it immediately. The nomination immediately had an impact on our ticket-buying public, on our Netflix-watching public, on our iTunes-downloading public. It was a huge performance-enhancing drug. And we’re going to get 10 seconds or 15 seconds, whatever you get, when your film is announced on the stage — the most coveted stage in the world, really — that’s going to make sure that people keep talking about the film, and that people who don’t know about it learn about it. And people are going to see it as a result … It’s crazy. My first film.

REALTED Our 2013 Oscar Predictions: Prepare For Your Betting Pool!

When you were making this, I assume you wanted it to reach as many people as possible. But in crafting it in your voice and in the voices of all of the people involved, did you think that you were speaking to a specific group of people? Or were you trying to spread it as far and as wide as you could?

DF: Well, I think the answer is ‘yes’ to both of those questions. I wanted to tell the story to people who didn’t know it. And that, in turns out, is just about anybody. Certainly, it’s everybody under the age of 35. And it includes a ton of people who were alive and conscious during the plague years in America, but who were deprived of knowledge of it by the miserable quality of reporting that was being done by the mainstream media on what was happening. Television news was doing a pretty poor job, for the most part. So, it was possible to be an American and really not know this was happening. It was possible to be a New Yorker and really not know this was happening. So, those audiences are coming to the film as well. I wanted to introduce this story in a way that was accessible to people just coming [to the story] for the first time. And I think that that has worked, that is working. People are introduced to it, and walk away with kind of a deep knowledge of what happened. And how the world that we have today was given to us in part by these guys and their activism.

In the wake of the growing success of this, are there any other projects or ideas that you’re planning on tackling? Either an expansion of this, or anything else?

DF: I am working on a number of documentary projects. And I am also finishing a book, which is a history of AIDS and AIDS activism. And I’ve got other AIDS-related projects that I want to spend some time with, also. To me, it was such a powerful and defining part of my life, that I’ve really dedicated my career in a really essential way to mining those years for stories of the people who lived through them, and trying to make sense of what those years brought … and what gifts come from something as dark as a killer and mysterious plague.

The ending of the film exhibits people who have gone on to do wonderful things and to live great lives despite being afflicted with the disease. I’m interested in your perspective on if you think that that gives too much hope. Even with all the medical advancements, AIDS does remain a serious disease. I want to know if you think that that propagates less of a serious attitude towards it? Or if there is a good way to meld optimism while still being realistic? Basically, I’m wondering what you would like to say about still being aware of the danger while not letting it inhibit you as it has in the past.

DF: I actually think in some really, really fundamental way, my film is not at all about prevention. Neither in a good way nor a bad way. HIV prevention is such a separate issue. There’s 55,000 people who get HIV in the United States every year. And that number has been exactly the same since 1995. Even before this breakthrough, 55,000 people a year, 55,000 people a year, 55,000 people a year. The film doesn’t address transmission because it’s its own issue. Nobody really knows how to impact those numbers through behavioral work. That work has not been accomplished in any way. One kind of quiet way the film addresses prevention is in its call at the very end to say that what these guys accomplished was to make it possible to survive HIV, but not necessarily probable. You still have to have access to these pills, and most people don’t. And it charges the audience with finding a way to get access to these pills to people in the developing world.

What the film doesn’t say, and what we now know, is this totally unexpected consequence of effective treatment of HIV: it renders people with HIV virtually non-infectious. So if, for example, you had HIV, and you were in treatment and you had an undetectable viral load, you are virtually no risk to any sex partners. Which is fantastic. We don’t talk about it, it’s just not being talked about. There’s been hoopla — over the summer, a lot of people were commenting over this declaration of us being on the verge of producing an AIDS-free generation. And that’s in part what they’re talking about. If we got these drugs into everybody, if we got everybody who needs the pills to take the pills — now, only a third of the people with HIV in the U.S. are on this medication, while everybody with HIV should be on them — if we got everybody on this, we solve that problem. We solve the problem of the epidemic. We would stop the spread, we would stop the dying, people would live near-normal lives, and infect nobody inadvertently. Those 55,000 cases, those are inadvertent infections. Those are people who don’t even know they’re HIV positive, passing it on to people who don’t know to protect themselves. If we find those people and put them on pills, that’s it. The epidemic is over. So that’s why the call at the end of the film is, ‘How do we get these drugs to the people who need them? Let’s find a way to do that.’

There’s such a wide variety of footage in this movie. How did you manage to apprehend everything?

DF: It was detective work. Just going from place to place to place, asking people if they had footage. And then if they did, preserving it. Because this is old video, it’s a very fragile medium. And then, if you preserve one library of footage, you can see in that footage other people with cameras. So then I would just do more detective work to find out who those people were. Whether or not they had survived the plague. And even if they didn’t, were their tapes still around? Did they have a lover who took care of them? Was the lover still alive? Ultimately, I was able to find footage either by tracking it from estate to estate to estate. People knew that there was something in these tapes that was essential and important. And lucky for me, they had been retained.

And can you talk about your experiences working with and learning from some of the people in the film, like Peter Staley and Larry Kramer?

DF: Although I knew these guys on the ground back then, I didn’t know them well. And they didn’t know me at all. I’ve gotten to know them through this process, and that’s been really rewarding. To meet people and have people in your life who are so accomplished, and who have made such a difference. That’s really amazing. I know that there’s been a kind of a reciprocity to that. They talk about the film as having brought them back to their own pasts, and having built a bridge between their present and their past that had not existed before.

That’s interesting — you talk about reaching people who don’t know about the story, this is people who lived the story returning to it through the film.

DF: And not really going back to it, but bringing that history into their present. At the end of the film, David Barr says, ‘A lot of us had a lot of trouble after.’ After ’96, what were their lives like? What were our lives like? There’s a lot of trauma, there’s a lot of unprocessed grief. There’s this tremendous burden of emotionality that we all carry, and have found a way to isolate or to wall off or to quarantine. And I think the film — as I understand it — for the folks who were in it, has helped to open quarantined space and process that past in a way that allows for a present.

The one scene in the film that keeps coming back to me is the crowd of people carrying the ashes and the bones of their loved ones to the White House lawn. To revisit that, having lived it…

DF: People who were at that scene — as I was — people who were there that day, in that mob, protesting in that dramatic way at the White House, have said to me after the film, ‘I forgot I was there. I forgot all about that.’ As powerful as that moment is, the death was so pervasive and people were so horrified and afraid and angry, that it all really blurred together. For some people, it became a kind of a molten mass of history, and the individual facets of it were indistinguishable. So I think it reestablishes a collective memory, and allows for that memory to exist in detail without doing harm. What the film tries to recall is that it was sad. It was terrible. It was terrifying.

But it was also invigorating. And it was also a time of great community and great love of one another and of oneself. This idea of self-love comes through so purely in the film, I think. That we were doing this for ourselves. I’m not going to just die, I’m going to try to do something. For me. And for the people I love, for the people around me, and for humanity. And that was incredible. I used to say that a lot of good came from the plague years. People didn’t know, really, what I was talking about. And I think this film shows some of that.

Follow Michael Arbeiter on Twitter @MichaelArbeiter.

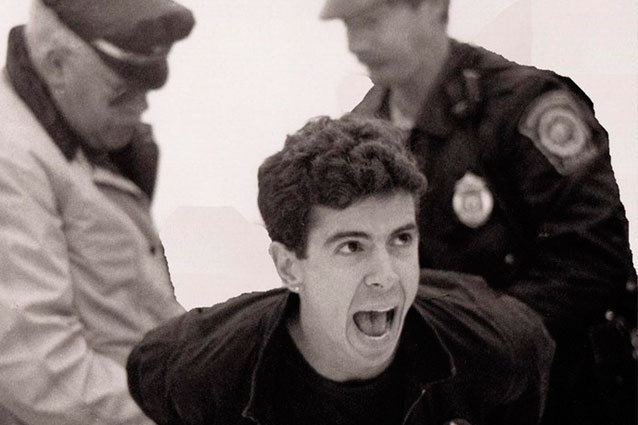

[Photo Credit: Angela Weiss/Getty Images; IFC]

Oscars 2013 Special Coverage

15 Most Iconic Red Carpet Dresses

15 Most Iconic Red Carpet Dresses

• We Predict the Winners: Do You Agree?

• 15 Oscar-Winning Nude Scenes

• The Worst Best Picture Winner Ever

• Oscar’s Problem With Pretty Boys

• Why Stars Should Fear Seth MacFarlane

• 10 TV Stars You Never Knew Won Oscars

• The Winner, According to You