“No good movie is too long and no bad movie is short enough.”

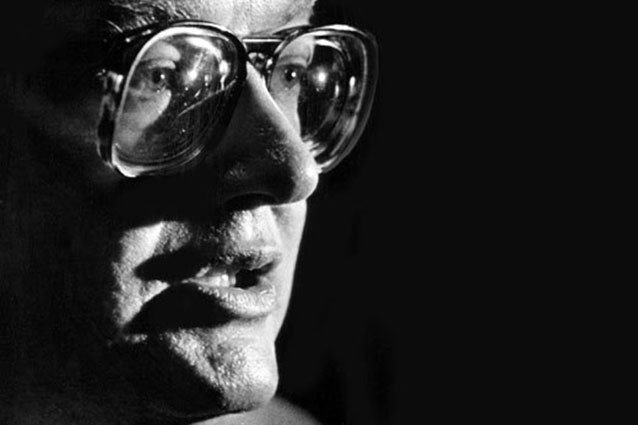

On Thursday, famed film critic Roger Ebert passed away from cancer — a shock to the large audience that followed his critical advice on a daily basis. His death came only days after a blog post ran in the Chicago Sun-Times, from which the above quote is pulled, that laid out his plans for the future. Although thyroid cancer and surgery had distorted the face of the man America knew from his popular film review show At the Movies, it never slowed Ebert down. According to the post, he clocked 306 movie reviews last year — not counting his numerous other blog posts and feature articles. That was just the surface for Ebert, who fostered other voices and added to the conversation on every level imaginable.

And that’s always been the case.

Prolificacy came naturally to Ebert. He was hired by the Sun-Times in 1967. While it was the place at which he ended his career, it was also the entry point for his emerging style and voice on pop culture. Browse Amazon.com and you’ll find that Ebert is a credited author of over 116 books, including his nearly annual Roger Ebert’s Movie Yearbook series, the Great Movies series, Scorsese by Ebert (an inside look at a famed filmmaker), Awake in the Dark (a compilation of his best reviews), and the infamous Your Movie Sucks: a highly regarded tome of the late author’s best pans. In 1975, Ebert became the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize for film criticism — an honor that’s only been bestowed four times since.

RELATED: Hollywood Pays Tribute to Roger Ebert

Ebert didn’t just pen “movie reviews” and cast them off into a sea of cineastes. He wrote for everyone, because he knew movies of all types could be enjoyed by everyone. It didn’t involved pandering, but a loose style that felt conversational and relatable. His jump to television was logical: reading Ebert was like talking to Ebert. So why not bring the act to the small screen? Ebert, along with his longtime sparring partner Gene Siskel, started Sneak Previews in 1975 as part of Chicago’s local public broadcasting station WTTW, and quickly became the highest rated show on the network. In ’78 the show was picked up by PBS and renamed At the Movies with Gene Siskel and Roger Ebert. In ’86, it moved up to ABC and became Siskel & Ebert & The Movies. The popularity filled a void in pop culture conversation as entertainment — it wasn’t a late night show, it didn’t bow down to Hollywood a la the Oscars, it wasn’t the local broadcast critics rounding out the nightly news, and it predated Entertainment Tonight and the E! network. Ebert and Siskel took the arguments people had at bars and put them on television. It was unheard of. It was captivating.

The ripple effect of At the Movies may be Ebert’s most important contribution. A wordsmith at heart, his television show was the gateway drug for pop culture fanatics and budding movie critics to take a moment and think. As he described it, film was important because it was “the most serious of the mass arts” and that criticism mattered because the movies mattered. That’s where his influence shows its face: sift through the millions of writings on the Internet and find a unique angle, a personal love letter, or an introspective account on any given film. Any given film — blockbusters, indies, foreign, homegrown, genres from any given point on the spectrum. They all say something, and Ebert not only started the conversations but promoted them. At the Movies was a starting point.

Ebert championed personal tastes. There wasn’t a “right” or a “wrong,” but there were movies he didn’t like and movies he adored. He was a man whose picks for the best films of their respective years included The Battle of Aligers, Apocalypse Now, Malcolm X, the sci-fi noir Dark City, and Synecdoche, New York. He would return to movies years later and reconsider them, even “hypocritically” (for those taking every choice he made as written in stone) ranking films above others — you won’t find any of the previously listed films 2012 Sight and Sound “Top 10 of all Time” list. And just because someone loved it, doesn’t mean he had to either. Roger Ebert hated Armageddon. Anyone who wonders why should read his review.

One of the major gripes against filmmakers is, “Why don’t you try and make a movie?” as if it’s necessary to know what goes into making a film to publicly wrestle, and occasionally knock, the ideas presented in one. While unnecessary, Ebert did that too. He penned Russ Meyer’s shlocky 1970 flick Beyond the Valley of the Dolls, reviled at the time but looked back as a twisted piece of pop art. While his “filmmaking career” didn’t pan out, Ebert remained steadfast in his role as an advocate for the arts. He wrote on the subjects that fascinated him, contributed to commentaries on DVD releases (he wasn’t joking about loving Dark City), and in the final years of his life, blogged about the smaller films that needed a boost while each week delivering insight into whatever was flooding the multiplexes. After his thyroid cancer and an eventual hip fracture that impacted his ability to walk, he continued to attend the Sundance Film Festival, a pastime for the film critic who helped turn the fest into what it is today.

RELATED: Howard Stern Has a Few More Words for Ebert

There’s no doubt that if Ebert had been able to vocalize his thoughts in later years, we would have seen more divisive, inspiring opinions from the critic. Vincent Gallo — whose Brown Bunny Ebert notoriously took to task for what felt like years after its debut at the Cannes Film Festival — is among the many to clash with the critic, but in the end, both filmmaker and critic were chasing the same goal. They wanted people to see and respect movies. Ebert didn’t want to hate a movie, but more importantly, he didn’t want people to misunderstand movies. He was ready to defend, as in the case of Better Luck Tomorrow‘s Sundance premiere:

At the Movies lost traction over the years, with the eventual loss of Gene Siskel and many alternatives to the show popping up on all mediums. Amazingly, that never felt like a hurdle for Ebert, even when At the Movies ended with Richard Roeper as cohost (and its short-lived revival produced by Ebert a few years later). Ebert launched his ship into the swirling microcosm of the Internet with little turbulence. He was a blogger at heart, ready to lay down thoughts on whatever topic he felt like. The politics of George W. Bush? Cooking? Video games? The last topic was one of his greatest conversation starters from the web: Ebert didn’t think video games were art. He made it loud and clear. He started a vicious Internet flame war. He was pleasant the entire time. (And he even jokes in his final post about his future with the medium, supposedly working on an At the Movies mobile game app, that he was ready to argue the artistic authenticity of whenever people were ready.)

RELATED: Robert Redford and Obama Ask: Is Gun Violence in Movies a Problem?

People, both in Hollywood and those who never met him, loved Roger Ebert. He’s been paid respects in all forms — few could help spoofing his rimmed glasses and “two thumbs up” catchphrase out of love, even Saturday morning cartoons. In 1997, capitalizing on his rare fame and support form his audience, Ebert began “Ebertfest,” his own film festival that played host to the “under-appreciated” films of the world, past and present. Fans gathered from across the globe to see Ebert’s picks. Even Patton Oswalt, upon hearing of Ebert’s death, noted that missing Ebertfest was a missed opportunity:

What I wrote when I had to cancel my EbertFest appearance.Now it’s one of my biggest regrets (link fixed):bit.ly/16tgyAT

— Patton Oswalt (@pattonoswalt) April 4, 2013

Enthusiasm was key to Ebert’s legacy. In the past, critics have pointed to his work as the “McDonald’s” of film criticism, quick and easy. But that’s mistaking Ebert’s style for pandering. Instead, his work made the heady concepts of dramatic theory into talking points that could educate anyone’s own cinematic vocabulary. A kid who spends every summer afternoon watching whatever the local theater is playing or scanning the cable airwaves or something remotely captivating was (will still be?) provoked by Ebert’s short but sweet reviews. They may push that kid to seek out “films,” try their hand at writing a “review,” or watch a movie and look past its surface elements to “understand what they mean.” Who is Frank Capra and why is Ebert namedropping him in a conversation on Eddie Murphy and Dan Ackroyd’s Trading Places? Seed planted.

Pop culture owes Roger Ebert for making demands, and anyone who takes in a movie, a TV show, a video game, a book, anything with an ounce of creativity put into it owes him for kicking them in the butt and pushing them to take it seriously. Ebert is no longer with us, but his dreams will be forever.

“So on this day of reflection I say again, thank you for going on this journey with me. I’ll see you at the movies.”

Follow Matt Patches on Twitter @misterpatches

[Photo Credit: Denver Post/Getty Images]