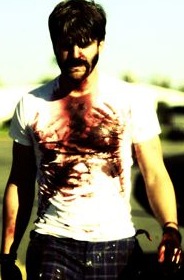

Once you see Bellflower, you’ll understand why the opportunity to speak to writer/director/star Evan Glodell is an exciting prospect. Glodell’s film is a sensory explosion, an amalgamation of sights, sounds and emotions that bring you into the lead character’s deranged mind, chew you up and spit you out. Bellflower‘s an unfiltered vision, one that splices flamethrowers, muscle cars, graphic violence and post-apocalyptic visions with romance, friendship and the human element.

Sound crazy? Duh.

I got to chat with Glodell, who I first met at this year’s Sundance and have crossed paths with multiple times over the last six months as he traveled across the country in his ass-whooping vehicle “Medusa,” spreading the good word of Bellflower. Finally sitting down to talk about the evolution of the film was well worth the wait:

Bellflower really picked up steam after debuting at Sundance. Why do you think the movie clicked with the audience at the festival?

I’ve never been through the festival circuit before. I never knew anything about it before this year. But from my point of view, they were the first ones who said they thought that our movie was valid. That’s the biggest thing that could have happened to us.

That’s always helpful.

We didn’t know many people, but we were trying to show our movie around. It’s almost identical to the [version] that is being released. We were showing it around, but nobody wanted to touch it. We had screenings for friends of friends that didn’t know us. They weren’t industry people, they were just regular people, but they all seemed to like it. Then we’d try to get it into someone’s hands in Hollywood, and they were like, ‘I don’t know about this,’ or even, ‘This is bad.’

People seem to identify the film with an alternative style of filmmaking, one you don’t find coming out of Hollywood. Why do you think it feels pleasantly foreign?

It’s a business. At some point, you’re not even watching movies for pleasure anymore. They’re really sitting there, analyzing them. If [the movies] aren’t close enough to what they’re expecting, they can be hard to think of at first. Whereas, if you were a little kid, you’d just watch it.

Is there an element in the film that audiences told you they’ve connected to that they don’t find in run-of-the-mill blockbusters?

Is there an element in the film that audiences told you they’ve connected to that they don’t find in run-of-the-mill blockbusters?

The honesty, I think. That’s the main thing I’ve heard. Also, there are the things that I get excited about. In the original idea, the way it came in, the structure is not entirely traditional. The first half really heavily focuses on this relationship building, and the second half kind of skips the relationship itself and takes it apart all of the characters’ experiences. When the idea first came to me, that felt different. It was so long ago now.

Where was the original idea born from?

Literally, I went through a relationship that was not unlike the one in the movie. At least, when it was happening, in the first half, I thought it was the best thing ever. Then, in the second half, when it started coming apart, it literally destroyed me.

You wrote, directed and starred in Bellflower—do you consider yourself one particular type of artist who dabbles in other forms, or do you just love it all?

[Laughs] Filmmaking and writing are the two things I actually enjoy doing.

And building cars, it seems.

Building cars, building cameras! Writing…the process of taking the writing and turning it into a movie, and also the hobby I’ve always had of building whatever seemed pertinent at the time—

Like cars.

The two cars for Bellflower that we had to do—I basically know about a thousand times more about cars than I did before I started this movie.

What came first: the cars or the movie?

The movie. The relationship I went through, then the idea for the script came in, then I wrote the script, and then some of those elements started coming into the script. Obviously, when the time came to make the movie, we had to make them real.

The film has a particular grit to it you won’t find in many films—usually because they’ll clean it up. You did it on purpose, by building your own cameras. Was that always the plan?

I think that was a natural progression for that element. I started experimenting with hacking cameras, building objects, all that stuff, quite a while ago. Everything I would shoot was always shot [with] stuff that I made. The more stuff I play with—and I’m always collecting more things—I started realizing I could make different looks. I’d been thinking about Bellflower for years before we started shooting it. Whenever I’d finish a project, or get a new camera, or a weird lens—or who knows what it was—I’d be like, ‘Oh shit! This is what we needed for this shot!’ The hobby of building cameras made me start thinking about what [scenes should look like]. I knew we were going to shoot this part of the movie on this camera to make it look this way… And with me and Joel [Hodge], we’ve been working together for years.

“Indie film” can get kind of a bad rap because of the tropes and baggage that come with the phrase. Bellflower is indie through and through, but was it a goal to pull a complete 180 from the indie scene?

“Indie film” can get kind of a bad rap because of the tropes and baggage that come with the phrase. Bellflower is indie through and through, but was it a goal to pull a complete 180 from the indie scene?

It was sort of a nonfactor in that I never really thought about it as far as comparing it. I just remember that all of us, me especially, wanted to make this movie, and I sort of had an idea of what it was going to be like. I was somewhat relentless in being like, ‘I don’t care if we don’t have money. This must be the way that we make a movie like this.’ That’s also one of the reasons that it do go how I would prefer. From the time we started shooting, it was three years—if you include the time I was working (almost full-time) on prep, it’s closer to four. Not everybody on the team was working full-time that whole time, but a lot of people were working a lot of the time. That’s why it took so long, and why it was such an intense project: an indie movie shouldn’t be able to have a crazy flame-throwing car. But we were like, “Damnit, we’re gunna get one!”

Maybe [indie movies] should have a flame-throwing car.

They should have at least one.

Nothing ever quite goes as planned when you’re making a movie on a shoestring budget and in a run-and-gun style. Were there any specific hurdles you had to overcome?

Obviously, the limited resources in general. There were a lot of things that we staged where I was like, ‘Shit, we’re gonna have to make a pretty big compromise in this.’ That’s one of those times when your ingenuity gets tested. You always hear stories about directors, like, ‘In this famous movie, we were supposed to shoot a scene at an airport, but then they couldn’t get the airport. And in the last minute, they did it in the bathroom.’ And now it’s a famous scene! And there’s always that pressure, like, ‘Dude, you can’t get a nightclub. You just can’t. You don’t have any money. You can’t get it. Think of something!’ And you’re wracking your brain. “I can think of something, right? I can think of something!” For me, occasionally I’d think of something and it would work out. Other times, I was like, “Okay, I wish I was clever enough, but I can’t think of something. So how are we gunna get a nightclub?” And you go back, and you fight, and you try and get smarter.

Drive a flame-throwing car into their parking lot, and suddenly they give you everything.

[Laughs] Yeah. You’re like, “Dude, check it out!” And they’re like, “Okay, you guys can shoot here!”

It’s a good bargaining trick. Speaking of challenges, with pressure mounting from directorial duties, did the idea of acting in the film ever feel overwhelming?

I think I had a really strong idea of what my character’s performance was supposed to be. I also didn’t know how I was going to get there, emotionally, as an actor—I don’t have that much faith in myself as an actor. For me, the acting was the hardest part. It felt like kamikaze. You’re running around like a crazy person, you’re making sure [everything] is working, you realize it’s impossible to get the shot with the equipment you have, you’re moving the lights…and then you have to get in front of the camera. You throw yourself in, and then it’s an intense scene. You’re supposed to do something that is so hard, and I know we only have a couple takes until we have to leave. I felt very pressured, but I understood that I had to go for it. There was a scene where I had to cry. The first take, I decided I was going to fake cry. I hoped to God that that was going to lead, three weeks later, to me actually crying.

Not to try and connect Bellflower to any films in particular, but are there movies that you go back to, connect with, identify as influences or just flat out love?

Anytime I see a movie where I can tell that the directors are being completely fearless—whatever the reasons are that they’re making movies, which you may never know, but you can tell they’re just going for it—I actually just a year ago found Gasper Noe. Those trip me out. There’s a couple of directors I think I found through him just recently. I would watch one of his movies, go on a blog, and see people say, “You liked that movie? Watch this movie!” I remember I went on a kind of a chain of different directors’ movies that started there. It wasn’t just French or Argentinian directors, it was from everywhere in the world.

So you saw Enter the Void?

Yes! I saw that recently. Apparently, the movies I was watching were like ten years old, and I had just heard of them.

I can’t deny the insane fun time of riding around in and blowing fire out the tailpipes of “Medusa,” But I have to say, I am quite partial to a car that you open the film with, the one that dispenses whiskey out the dashboard.

A lot of people have said that they like that one more. It’s a totally different thing, right? One is for intimidation, and not really made for comfort. The other is like a lounge car. You can cruise around and have drinks. It’s all open, and white, and bright, and nice in there.

So you’re well into the writing process for future movies. Now that Bellflower is in theaters, are you moving directly into something else right away?

Yeah. I have this script that I’ve been working on, on and off, for a year and a half. I haven’t shown it to anyone yet. But the second everything is done with Bellflower, I’m going to lock myself in a room for a couple of days, read it over, and make sure I’m happy with where it is. Then I’m going to start talking to different people who have expressed an interest in helping.

Does it have flame-throwing muscle cars in it?

That is actually a very good question. I think, very likely, it will have at least one.

Yes! That’s all I need to know. Perfect. My last question is, do you know how many crickets a person can eat before they die? Because I’ve seen you eat a lot of crickets. Both in person and on film.

I don’t know, but Jesse [Wiseman] deserves the credit for that. At this point, she has eaten more crickets than anybody I know.