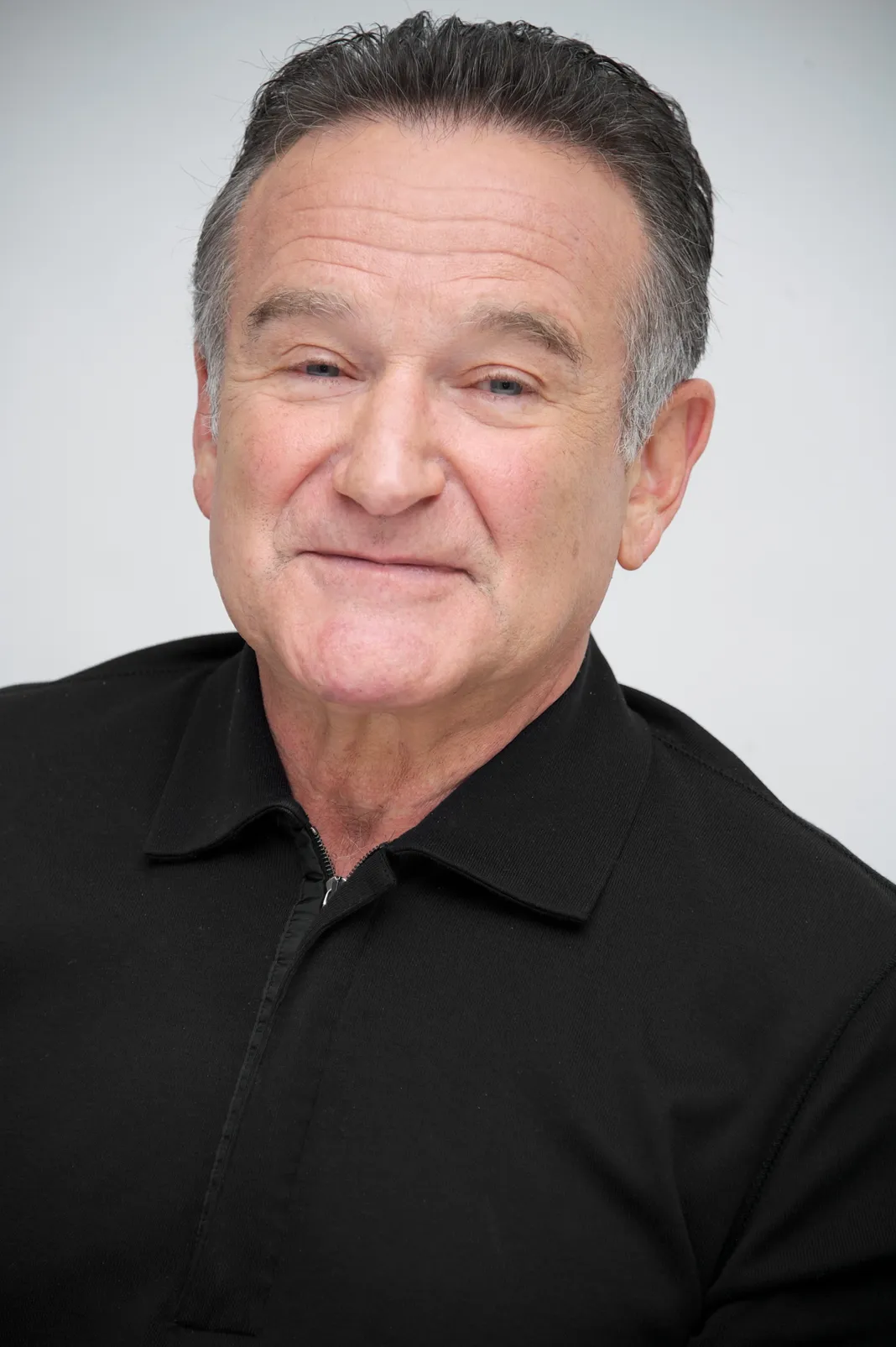

Getty Images/Vera Anderson

Getty Images/Vera Anderson

I was humming a tune from Robert Altman’s Popeye, a terribly underrated feat of Robin Williams‘ comedy (and his first cinematic role), when I read the news of the actor’s passing. Hastily, I diverted attention to the public sphere, rushing through the social media posts of friends, colleagues, and strangers, hoping for a taste of which Williams roles most touched the lives of each and every individual vocalizing grief. I knew there would be no shortage of reference to Williams’ dramatic work — his Good Will Huntings and Dead Poets Societys — but of course my expectation was to find the principal focus on his comedy. More than an actor was Williams a comedian, whether he be playing on stage, on television, or on the big screen.

So it was an especially jarring turn to discover, when I launched back from the tributes to ingest more information, just how Williams died: authorities had begun calling the incident a suicide. Only for a moment, though, was I so rattled in surprise. Williams’ endeavors with rehab for drugs and alcohol, both this summer and earlier on in the 2000s, were no secret. But more significant than this is the fact that nobody is or isn’t “the type” to take his own life; nobody should be a more surprising victim of suicide than anybody else. Stigmas to the contrary are a large part of why depression is such a treacherous epidemic in our world and country.

Upon learning of Williams’ death, some are bound to consider the dichotomy between the man we knew — the one who’d dress in drag and howl in a Scottish accent, who’d roar through the radio waves of the Pacific Rim — and the man in earnest. Some might doubt that the Williams we met as Mork, loved as Patch Adams, played with as Alan Parrish, and wished upon as the Genie, was anything whatsoever real. Anything more than “for the cameras.”

It certaintly was. It was a Williams for us. From him.

Upon perusing Facebook and Twitter and speaking with friends, I found something you don’t often see when a beloved actor dies: variety. Every other voice had a different Williams role to celebrate, ranging from the wacky Aladdin, the sweet and schmaltzy Hook, the stern and sincere The Birdcage, the dark and severe Insomnia, and the esoteric The Fisher King. The constants were affection and familiarity. More than a few folks who grew up in the ’80s and ’90s likened Williams to a distant family member, or even a surrogate father. Clearly, the man had fostered an incredibly, unprecedentedly intimate presence with a generation of film and television watchers.

And each of those “types” of Williams is just as valid as the next. As such, the “type” of Williams we — the public — all collectively know is as valid, as palpable, as real as anything that he might be beyond the limelight.

A friend of mine expressed consternation over the proper decorum in situations like these: is it tacky to expose your grief for a passing friend whom you’ve never met, who never knew you? It doesn’t seem to be — although it would be tacky to presume that I know anything of what Williams might or could or should want, we can rest assured that he brought his talents, his hobbies, his self into the world in the way he did in the hopes of making us laugh. Few comedians, and even fewer actors, of our generation could be deemed so potently invested in the happiness and enjoyment of their audiences. In every one of his movies, Williams was giving us a very big, powerful, important part of him. That, and all the laughter that came with it, was for us. So it doesn’t seem all that off base to think that we couldn’t share every feeling of love and sorrow we might have about him.

Finally, we return to the question of authenticity — what about the man behind the laughter? The man so stricken with pain? The “real” Williams?

That’s where the danger comes in: the thought that only the morose can be depressed, that anyone so capable of earning a laugh must be riding a permanent cloud nine. That Williams’ humor was the result of a chemical reaction with celluloid, and would dissipate immediately upon production wrap. Williams, like many depressed men and women, was a man who liked to, maybe even lived to, joke. A man who could command any room, nail any impression, or knock out any punchline. Granted, Williams can probably do this a lot better than the vast majority of folks out there, depressed or otherwise. But he’s not a unique breed. There is no discernible breed. Depression and the turmoils that come with it can inflict anyone: the funny, the mopey, the angry, the brawny, the silly, the sensitive. From your Sean Maguires to your Daniel Hillards.

It often takes a stride to learn that the depression living within any of these people can be real. And for those who suffer with the disease, it is just as difficult, if not more so, to understand that the rest of you — the funny, the sweet, the strong, the “Seize the day!”, the “Beee yourself!”, the “Hellooo!” — is, too, very much real. No matter which side of the equation you might be on, you have one more lesson here to learn from John Keating:

We did know the real Williams. We just didn’t know every part of the real Williams. We might not have known the real pains, the tragedies that too many people face alone and don’t have to. But we knew something just as real: his ability and his drive — no, his insistence — to make the world laugh. And yes, he made the world cry plenty. When he battled for a soul in Bicentennial Man or delivered special peace to a hospital of sick children in Patch Adams or dragged Matt Damon out of his own carnivorous guilt in Good Will Hunting, he made us cry. But the Williams that made us laugh… the one who splashed his face with pie frosting, babbled around Sweethaven in a feverish stupor, and doled out life lessons to a wannabe prince via obscenely anachronistic pop culture references… well, that’s my real Williams. And he’s just as real as anybody else’s.