Minor spoilers for The Dark Knight Rises follow.

Minor spoilers for The Dark Knight Rises follow.

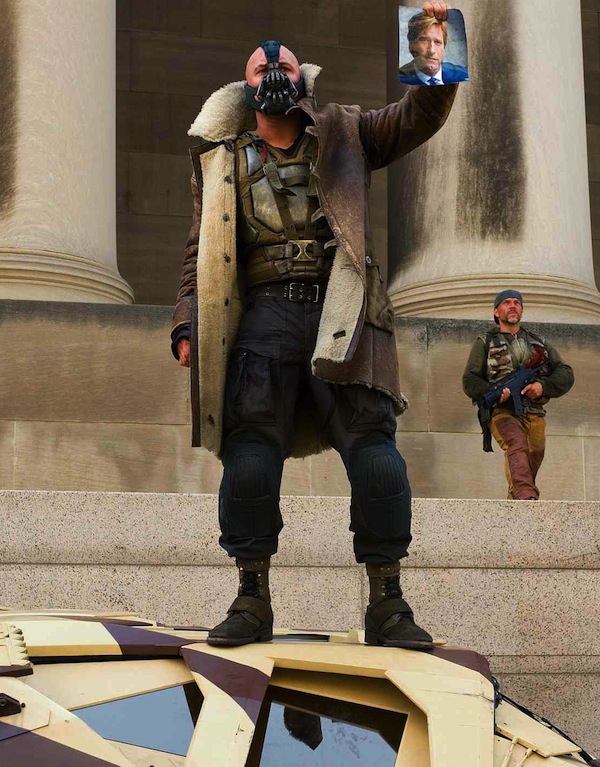

When Christopher Nolan decided to take the filming of his final Batman movie, The Dark Knight Rises, to downtown Manhattan in late 2011, he opened Pandora’s Box. At that moment, the location was synonymous with one of the biggest grassroots movements our country has seen in the last decade: Occupy Wall Street. Months later, the first major trailer landed, featuring Selina Kyle (Anne Hathway) whispering “A storm is coming … you’re going to wonder how it is that you lived so large for so long and didn’t leave enough for the rest of us” in Bruce Wayne’s (Christian Bale) ear, scenes of violence in the streets, and the stock market flashed intermittently. Suddenly, The Dark Knight Rises wasn’t simply the epic conclusion to a series we’ve all followed rabidly; it was a direct commentary on the OWS movement — reality of the story’s actual origins in the French Revolution be damned. Out of that apparently inescapable connection comes a confounding question: where does Batman stand? Is he the 99 or one percent?

By now, most of us know consciously that the film’s premise and OWS are independent of each other and in truth, any real connection between the two movements dies with revolutionary Bane’s penchant for violence and mayhem. Perhaps that’s why Nolan has worked so hard to express that the film is not in any way associated with the movement, instead pointing to its roots in Charles Dickens’ A Tale of Two Cities. Equating Bane’s upheaval to the OWS movement in the real world would be an unflattering comparison, a sentiment Occupy Chicago activist Michael Ehrenreich shares. He tells Hollywood.com, “As far as OWS is concerned, [Nolan] seems to regard populist uprising negatively, judging by the reaction of Catwoman to the excesses of the ‘revolution’ and the kangaroo court Cillian Murphy presides over … It’s hard to tell where the Nolan brothers’ political allegiances lie, but it’s hard to see a positive portrayal of OWS in this film.”

But the film isn’t actually making any comment on the real-life movement. As TDKR producer Michael E. Uslan says, “The film is emotionally impactful and thematically important.” It’s not aimed at any specifics of modern U.S. politics. But while filmmakers have reiterated that fact time and again, the echo is hard to silence. That’s because none of us can avoid the fact that the issues of both the film and the OWS movement are unavoidably connected.

“Nolan directly confronts the issue of income inequality, corporate malfeasance and, to a small extent, police overreach,” says Ehrenreich. “We all know that the script was written and most of the principal footage was shot before the outbreak of OWS, but these are ongoing political questions, especially since the 2008 crash,” he adds. While the film drops its big ideas when Batman eventually saves the day in a blaze of assumed martyrdom, Nolan’s film weighs those political and social questions. We encounter the notion of Gotham’s inhospitable environment nurturing a new class of desperate, downtrodden criminals, forced to formulate their plan below the city streets in the sewer system. These unfortunate souls join the ranks of Bane’s revolution forcing us, the audience, to contemplate the society circumstances that led them there. We find a shiny politician Harvey Dent being wrongfully upheld and memorialized in order to promote his act, which wills Gotham into a police state and eschews the usual due process in order to eradicate crime.

The film also offers up the larger question of pursuit of wealth versus humanity, showing characters who seek nothing more than money as weak pawns in Bruce Wayne’s, Selina Kyle’s, and Bane’s plans. Bane even responds to a Wayne Industries board member’s cry that he paid him “a lot of money” with the retort, “And this gives you power over me?”

To some extent, the film upholds the starry notion of achieving the American Dream, the childlike idea of being all that we can be. When Bruce makes the impossible climb out of the subterranean prison, Selina finally manages to wipe her slate clean and live happily with Bruce. We also see it to some extent when Officer John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) makes his meteoric rise from former orphan and police peon to Batman’s successor rising up into the Batcave.

To some extent, the film upholds the starry notion of achieving the American Dream, the childlike idea of being all that we can be. When Bruce makes the impossible climb out of the subterranean prison, Selina finally manages to wipe her slate clean and live happily with Bruce. We also see it to some extent when Officer John Blake (Joseph Gordon-Levitt) makes his meteoric rise from former orphan and police peon to Batman’s successor rising up into the Batcave.

But a proliferation of thematic and topical similarities doesn’t necessarily create a bridge between OWS and TDKR. Professor Bryan Waterman of New York University, who specializes in New York literature and history including Frank Miller’s The Dark Knight Returns, says that while the connection seems obvious, it’s actually a stretch. “Conservatives will make the same easy connection and think Bane represents Occupy. But even though the scenes of police clashing with scraggly punks on Wall Street may bring up recent memories of similar events, Bane’s crowd resembles OWS even less than Gotham’s virtuous police force under attack resembles the NYPD.”

To be fair to those who might find contemporary issues in the plot, the events in Gotham and Batman as a character have always been difficult to get a definite read on, especially in Nolan’s complex film series. “The Nolan movies don’t offer any easy political readings … Starting as he does from a question that takes the Batman legend seriously — What does it mean to make a mentally damaged hero a figure of American justice? — the film led to all sorts of conflicting readings of Nolan’s hero,” says Waterman.

In the weeks after The Dark Knight was released, Batman/Bruce Wayne endured a bevy of theories about his political stance. His ominous sonar/wire-tapping device encroached on the privacy of an entire city, but he created it in order to stop the Joker. Could this be a metaphor defending George W. Bush for his tactics in executing his war on terror? Similarly, it’s Batman’s decision to uphold Dent in the public eye, which then provides a foundation for the Dent Act in The Dark Knight Rises, which in turn makes Gotham into a police state. By this logic, Batman is a de facto advocate for tighter government control, yet he operates outside of it. So, can Bruce Wayne be a strictly conservative hero? Do his methods make him a symbol of the wealthy and powerful?

Not necessarily. Wayne treads a very murky line between the wealthy and the disadvantaged. On one hand, he’s born into privilege but he’s robbed of his parents as a young boy, thus struggling to adulthood as an orphan. The character, especially in TDKR, serves as both a benefactor and supporter of the culture of wealth within Gotham and a beacon of hope to the young displaced boys at the St. Swithin’s home, including grown orphan John Blake.

Political blogger Jim Newell has an idea about why this back and forth is so difficult. “It’s hard to look at the politics of superheroes because superheroes, in general, are very illiberal. The solution to problems is never having people organize and find out solutions democratically. It’s always about turning power over to one sovereign who solves it himself, so it’s very paternalistic,” he says.  It’s true, Nolan’s Batman operates under the notion that he’s “whatever Gotham needs me to be,” but it’s largely Batman who’s deciding what it is Gotham needs and it’s his wealth and resources that determine the outcome. It’s a problem Ehrenriech sees with the hero as well. “Batman represents the belief that we need elites, that we need representatives, that we depend on the rich and powerful,” he says.

It’s true, Nolan’s Batman operates under the notion that he’s “whatever Gotham needs me to be,” but it’s largely Batman who’s deciding what it is Gotham needs and it’s his wealth and resources that determine the outcome. It’s a problem Ehrenriech sees with the hero as well. “Batman represents the belief that we need elites, that we need representatives, that we depend on the rich and powerful,” he says.

But despite the criticism that Batman puts us in a situation of deferring the solutions to a few members of the wealthy elite, he still has the super human trait that helps to serve as the great equalizer: his humanity. “Nolan’s Gotham is so real … we believe in this man [Bruce Wayne] and we believe in this city,” says Uslan. Bruce’s constant inner conflict and his desire to do good amid his wealth of multidirectional traits creates a unique phenomenon for those looking to dissect the hero. “He’s a blank slate … we project our viewpoints onto Batman,” says Uslan.

We see this in both film and comic form in Frank Miller’s 1980’s revival of the Dark Knight. Batman occupies a space that’s not as easy to situate in a socio-political context. On one hand, he upholds the notion of tight control and regulation in the city of Gotham, policing its streets through heavy surveillance and excessive force. He’s a seeming advocate of tight municipal control. On the other hand, he’s strongly against gun violence — a reaction to his parents being killed at gunpoint — and he operates outside of the city governments laws, acting as a vigilante when governmental measures prove ineffective. His acts are in some ways selfish, as many Gothamites see him as the instigator of the dangers that plague the city while others insist he’s simply brave enough to fight against the wave of crime and fear in Gotham that most of the public has accepted as part of the immovable landscape.

Batman complicates his position a bit further in The Dark Knight Rises when he loses his fortune, essentially joining the 99 percent. He finds himself in a prison lodged deep below the earth’s surface, with a tower he must conquer with only his personal might and perseverance in order to regain his position as Gotham’s savior and Dark Knight. (If that’s not a metaphor, I’m not sure what is.) In that respect, while his inherited wealth is technically what got him to this point, it’s his own blood, sweat, and tears that allow him to truly earn back the position and act as a savior.

If these elements add up to anything, it’s that Batman’s not a character that actually fits into one category or the other, and if his constant bouts of self-doubt and reflection are any indication, even he’s not sure where he fits in the grand scheme of things: the only part of his character that we can really hone in on his humanity. Thus, our interpretations are bound to be determined by our own views as we process the idea of the caped hero.

While he is not easily categorized, Batman/Bruce Wayne does feel more real than many of our other fictional, flying saviors. Perhaps that’s why we strive to find so much political significance in his adventures. However, just as Bane’s revolution is more of a thug’s anarchic initiative than a reference to OWS, Batman is not a hero for one side or the other, but rather the hero for the occasion. His millions do not make him a member of the one percent any more than his status as an orphan makes him a member of the oppressed 99 percent. He is as he promises, simply “the hero we need him to be.”

Follow Kelsea on Twitter @KelseaStahler.

More:

‘Dark Knight Rises’ Producer Michael E. Uslan and the Epic History of Batman

‘Dark Knight Rises’: A Fitting Franchise Finale?

Batman Beyond: ‘Dark Knight Rises’ and Rebooting the Caped Crusader