[SPOILER ARERT: This article contains spoilery information from the novel Perks of Being a Wallflower and its film adaptation. If you do not wish to be spoiled, please stop reading.]

[SPOILER ARERT: This article contains spoilery information from the novel Perks of Being a Wallflower and its film adaptation. If you do not wish to be spoiled, please stop reading.]

The Perks of Being a Wallflower is the kind of book that people love. The ultimate bildungsroman, Perks has attracted new readers consistently since its release in 1999. With each wave of new readers, more and more teens have fallen in love with Charlie, Sam, and Patrick. For kids on the precipice of their high school experiences, Charlie’s story is their story. For older teens, the unknown that will face Patrick, Sam, and the rest of the “misfit toys” when they graduate is all too familiar. But, beyond the plot, it is author Stephen Chbosky’s masterful voice that really hits home. He tells Charlie’s story with such grace, empathy, and poignancy that it is near impossible to read the novel without internalizing and relating to these characters’ struggles. Luckily for the novel’s vast legion of fans, Chbosky is at the helm of its film adaptation, and he has poured every ounce of the book’s truth and honesty into its 103 minutes.

Turning beloved young adult novels into successful movie adaptations is a tricky business. Unfortunately, when it comes to quality and adherence to the source material, there are far fewer Harry Potters than there are The Golden Compasses. But with Chbosky behind the camera, Perks fans were confident that their baby (which, lest we forget, was Chbosky’s baby first) was in good hands. However, achieving one’s vision is not always as easy as dreaming it up; and we all know where the road paved with good intentions leads. Would Chbosky, who has limited experience as a screenwriter, director, and producer, live up to his fan’s — and his novel’s — high expectations? In a word, yes.

While Perks occasionally veers from the source material’s plot points, Chbosky and his young cast are able to recreate the novel’s tone perfectly. The movie expertly captures the book’s sense of immediacy and the heightened anxiety of its adolescent protagonists. But, much like the book, the film finds moments of peace and beauty amidst the angst. One of the novel’s enduring images is of Charlie, Sam, and Patrick hurtling through the dark tunnel in their pickup truck towards the bright city lights on the other side. Chbosky writes,There’s something about that tunnel that leads to downtown. It’s glorious at night. Just glorious. You start on one side of the mountain, and it’s dark, and the radio is loud. As you enter the tunnel, the wind gets sucked away, and you squint from the lights overhead. When you adjust to the lights, you can see the other side in the distance just as the sound of the radio fades because the waves just can’t reach. Then, you’re in the middle of the tunnel, and everything becomes a calm dream. As you see the opening get closer, you just can’t get there fast enough. And finally, just when you think you’ll never get there, you see the opening right in front of you. And the radio comes back even louder than you remember it. And the wind is waiting. And you fly out of the tunnel onto the bridge. And there it is. The city. A million lights and buildings and everything seems as exciting as the first time you saw it.This description, which comes near the end of the novel, is of course a metaphor for the ostensible hopelessness of adolescence. Feeling alone and afraid, you can hardly breathe, the pressure to know and find yourself is so great. But then, right when you think you can’t take it anymore, you are released from the uncertainty and confusion into the brilliance of self-acceptance. It may be cheesy, but who hasn’t felt that? On screen, the relief this scene depicts is felt viscerally. You watch Emma Watson — arms outflung to embrace the night, her beautiful smile lighting up the screen — fly through the tunnel’s foggy, dreamlike palette and goosebumps form on your skin (or at least they did on mine). You may have never ridden in the back of a pickup truck at night, but you know how Watson’s Sam feels. Charlie’s indelible words, “I feel infinite,” ring true in their hyperbolic simplicity.

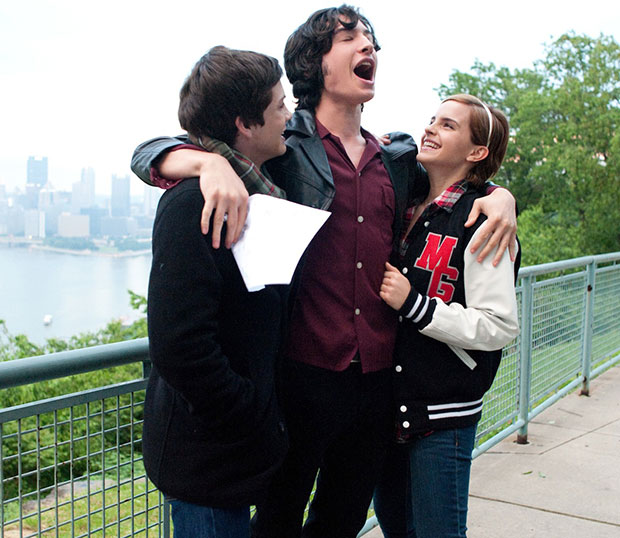

While Chbosky’s direction and adapted script undoubtedly play a role in allowing the film to stay so true to the book, credit must be given to Logan Lerman (Charlie), Ezra Miller (Patrick), Emma Watson (Sam), and Mae Whitman (Mary Elizabeth) for diving into their characters with such abandon. The young actors bring their characters to life with just the right amount of sweetness, innocence, and misplaced pretension. As in the book, the film paints rich portraits of each character, with no prejudice towards screen time or placement in the credits, and the film is better for it.

Fans looking for a page-by-page adaptation of the novel may be slightly disappointed to see that certain arcs don’t make their way on to the screen. Candace’s pregnancy and abortion is omitted, as is the rape that Charlie witnesses as a younger child and the prevalence of physical abuse in Charlie’s family history. We also don’t see Charlie and Patrick’s nighttime visit to the park parking lot. But for me, these were smart edits to make. In this film, as in any book to movie adaptation, you face time restraints that make cuts necessary. But beyond that, these cuts help keep the movie from crossing into melodrama territory (a line it already precariously walks). As in the novel, The Perks of Being a Wallflower film tackles heavy topics such as suicide, child molestation, closeted homosexuality, and teen drug use. Do we really need to add abortion, rape, and physical abuse to this list? Chbosky was wise to let these story lines fall by the wayside.

Fans looking for a page-by-page adaptation of the novel may be slightly disappointed to see that certain arcs don’t make their way on to the screen. Candace’s pregnancy and abortion is omitted, as is the rape that Charlie witnesses as a younger child and the prevalence of physical abuse in Charlie’s family history. We also don’t see Charlie and Patrick’s nighttime visit to the park parking lot. But for me, these were smart edits to make. In this film, as in any book to movie adaptation, you face time restraints that make cuts necessary. But beyond that, these cuts help keep the movie from crossing into melodrama territory (a line it already precariously walks). As in the novel, The Perks of Being a Wallflower film tackles heavy topics such as suicide, child molestation, closeted homosexuality, and teen drug use. Do we really need to add abortion, rape, and physical abuse to this list? Chbosky was wise to let these story lines fall by the wayside.

Conversely, I would have loved to see other condensed scenes — including Charlie’s relationship with his English teacher and his family’s complicated web of support and repression — more fully explored on screen. Mostly because the small glimpses we get of these are so wonderful. Your heart aches as Charlie’s teacher, Bill (Paul Rudd), seeks to show Charlie that he is special, and as Charlie’s parents (Dylan McDermott and Kate Walsh) struggle to understand their son. But the film’s biggest hole in terms of its adaptation is the downplaying of the significance of Charlie’s reading list. In the novel, Charlie’s reading of the books Bill gives him — from Peter Pan to The Catcher in the Rye to The Fountainhead — helps shape his understanding of the world, and ours of him. The novels provide Charlie with a sense of support and understanding; they show him that he is not alone. And Charlie, meanwhile, assures the audience this same thing.

Charlie’s story of growth and personal discovery has become a roadmap for generations of teens because of its universality. Who hasn’t felt alone, neglected, or misunderstood? Which, in the end, is why Charlie’s story resonates just as well on the screen as on the page. In the film as in the novel, Patrick raises a glass to toast Charlie and says, “You see things and you understand. You’re a wallflower.” In Chbosky’s film, we are able to see Charlie, and understand ourselves.

Follow Abbey Stone on Twitter @abbeystone

[Photo Credit: Summit Entertainment]

More:

‘The Perks of Being a Wallflower’: Join Emma Watson’s Clique — VIDEO

How ‘Perks of Being a Wallflower’ Author Did it All for the Movie