Tower Heist might speak particularly well to the present day, with a plot revolving around an eclectic bunch of everymen trying to steal back the money that is rightfully theirs from a greedy billionaire. However, there is one pretty significant element of Tower Heist that has been a constant for generations (not Casey Affleck, although I do have my suspicions that he is a reincarnation of Johannes Kepler).

Tower Heist might speak particularly well to the present day, with a plot revolving around an eclectic bunch of everymen trying to steal back the money that is rightfully theirs from a greedy billionaire. However, there is one pretty significant element of Tower Heist that has been a constant for generations (not Casey Affleck, although I do have my suspicions that he is a reincarnation of Johannes Kepler).

I’m talking about comedy. Although comedy has been around since the dawn of humanity and has existed as a prominent part of film, television and other forms of popular culture over the past few decades, there are certainly distinctions in the way comedy has been delivered. This is something that Tower Heist embraces.

Upon examining the cast of Tower Heist, you’re likely to notice the wide range of ages in the starring players. More importantly than their ages even are their professional histories. Headliner Ben Stiller, for instance, developed his notoriety in the 1990s. Stiller’s Tower Heist sidekick Eddie Murphy, who really blossomed a decade prior—the 1980s. And, of course, the film’s villain: the great Alan Alda, who became a welcome fixture in American households during the 1970s with the hit television series M*A*S*H.

Each of these men is synonymous with the comedy of his time. Alda’s heartbreaking M*A*S*H finale still holds the record for most-watched episode of television in American history. Murphy’s Coming to America and Beverly Hills Cop movies are modern classics. And Stiller has continued to churn out fan favorites since his 1995 comedy Heavyweights. And though each could be considered a comedic kingpin of his respective era, they are all quite different in the humor with which they do supply us.

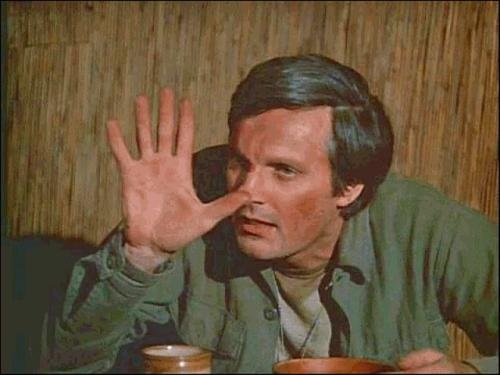

Let’s start with Alda (I like my lists to be chronological, alphabetical, and in descending order of time spent grinning). Alda is known best for having played army surgeon Captain Hawkeye Pierce for eleven years on M*A*S*H, regaling audiences with his charm and intellect. Pierce acted as sort of a less energetic Bugs Bunny figure—we always know that when up against opponents like the humorless Major Burns, Pierce would come up the victor. Why? He was smarter, cooler, quicker with a jab—always one step ahead of everybody else. Pierce was rife with wordplay, double-talk, and countless of lines that seemed to entrance the seemingly endless supply of nameless military nurses at the 4077th.

In short, Pierce was a winner. This is why it was easy to root for him—he’s the sort of character that everyone wishes to identify with the most (even if they are more the Radar type). And most importantly, just about everything he said was funny. Always on point and stocked with a clever shot, Hawkeye Pierce—and his portrayer Alan Ada—represented the comedy that America needed in the trying times of the Cold War: someone who represented intellect, popularity, stability, and success.

Eddie Murphy represented quite a different style of hero—not quite an antihero, but definitely a less “noble” figure than Hawkeye. Murphy’s 48 Hrs. conman Reggie Hammond and his free-wheeling Beverly Hills Cop detective Axel Foley were reckless, irresponsible, loud-mouthed goofballs: the type whose energetic antics were regularly laugh-a-minute. The main difference between Murphy and Alda is the level of composure each represents. Whereas Alda’s comedy derived from his ability to stay calm in high stress situations (minor example: the Korean War), Murphy was a wily stick of dynamite, set off by so much as a crooked glance from somebody wearing far too much denim.

For my money, Trading Places is the best comedic performance by, and best representation of, Murphy. When the film begins, Murphy’s character Billy Ray Valentine is a squawking swindler, pleading unsuccessfully with Philadelphian pedestrians for some spare change. Before becoming involved in the Duke brothers’ nefarious scheme (the central plot), Valentine finds himself in over his head in a handful of situations: he is outsmarted by a pair of policemen, thrown in jail, and nearly beaten to a pulp by two very large, very intimidating cellmates. And this is Eddie Murphy at his best: while Valentine manages to dig his own grave deeper and deeper, he still hangs onto the air of superiority and self-importance that fuels the vociferous verbal tirades for which the actor is famous.

Alda’s type was important for his time—when America needed to feel like a winner. Murphy’s was equally important for his time. Murphy’s criminal characters didn’t represent the same educated sophisticates that Alda’s did. Murphy played on behalf of the common man who, while perhaps not as prone to Pierce’s casual literary allusions and effortless yet hilarious asides, were still capable of being extremely funny, and were still capable of being looked at as heroes. Hawkeye Pierce was a winner, and he knew it. Murphy’s characters weren’t quite as adept as Pierce, but they were nonetheless convinced of their grandeur. And then comes the third comic actor in question, whose characters represent the final extreme: the beta-male, the hapless nebbish, the spineless nerd, the full-fledged, bona fide loser…too harsh? It’s okay…as you’d probably assume from the fact that I blog about movies for a living, this is the category I belong to.

The ‘90s saw America willing to root for a new type of hero. While Radiohead, Daria and Stephen Chbosky let the lot of us know that there was value in our inability to fit in, Stiller brought the notion of this new hero to comedic film. With films like Reality Bites, There’s Something About Mary, and Meet the Parents, Stiller represented the sort of well-meaning sad sack that we both pitied and rooted for. American pop culture wasn’t as consumed by superiority by this point. Weaker characters could be our heroes. We would even find ourselves comfortably—willingly, even—identifying with the losers.

As Alda’s charming soldier was necessary for the American public in the 1970s. Murphy’s lovable ne’er-do-well was a heroic character for the working class man of the 1980s. And for the brooding beta-males who hadn’t yet seen their hero come to fruition onscreen, the 1990s brought Stiller.

So what does it mean for us that they all come together in Tower Heist? It could mean the beginning of the end to the rigidity in the separation of these types of heroes. Maybe we can find ourselves rooting equally for men like Hawkeye Pierce, Billy Ray Valentine and Michael Grates. After all, the most heroic thing done by any of these characters is the inspiration of laughter in their audiences. When casting out the value in those unlike us, this is one of the most important things to remember.

It doesn’t matter if you relate best to Alda’s well-read playboy war hero, Murphy’s motor-mouth swindler or Stiller’s sighing sad sack. The important thing is that each of these men can, has, and will continue to make us laugh.