This piece is adapted from a post originally published on the author’s Substack, “How to Have Fun in the Apocalypse.”

At least one Sunday a month, my husband and I go to the central plaza of the Santa Maria la Ribera neighborhood of Mexico City where a group of senior citizens dressed in their slick and flashy best dance to cumbia sonidera, tropical son, danzón, and salsa tracks spun by a DJ named Sonidero Sincelejo. We go to watch and dance and generally to soak up the joy.

The old people who dance in the park are happy and they are gorgeous and they are incredible dancers. Each one of them is old enough to have been beaten bloody by grief at some point or many, and still, they’re dancing. It gives me hope that when I’m old, I’ll be dancing, too. It gives me hope that doing things I love will still make me smile huge and feel alive. People stop and sit and watch for periods and they smile and clap and whistle in admiration. And they’re OK. While the old people dance, everyone in that corner of the plaza, every person with all of their pain and sorrow is just fine, at least for that moment. The whole scene is a testament to the human capacity for sharing joy in the face of life. And I can’t think of anything people need reminding of more than that. Especially now.

This weekly gathering has been happening for 13 years in the same place. It’s a sacred scene: popular culture taking place in public space. And it’s under threat, along with all of the similar gatherings in plazas all over the city.

One may assume the threat is that the dancers are primarily very old. In many places around the world, traditions die out as younger generations prefer global culture––TikTok dances to tarantella or tango. But no. Actually, cumbia and sonido culture is experiencing a resurgence in popularity.

Sonideros aren’t just DJ’s. They bring lights, signage, and have a particular culture of talking over the tracks, shouting out their people, their community. They create sonidos, which are a whole event. In Mexico City, starting in the 1960s, sonideros would travel all over South America and the Caribbean bringing records to Mexico. They were responsible for much of the spread and mixture of many genres of Latin American music. In the 1970s, they started throwing huge sonidos. They would close off streets or set up under overpasses for entire days and hundreds of people would come to dance.

By the 1990s, Mexico City police started shutting them down, often violently, in full riot gear. But the culture survived, and sonidos are back in style. Young people are carrying on the tradition. The federal government even planned a series of events to promote sonido culture over the last few years, and this year, officially recognized it as immaterial cultural patrimony. Young sonideros proliferate, carrying on the tradition. These days they’re even playing bougie events like Art Week.

So why, at a time of renewed interest in this culture, is a group of old people who dance in a plaza on Sundays under threat? The answer is long, complicated, and reflective of the many dynamics at play in modern Mexican culture.

That time the borough president sent in goons to stop old people from dancing in a park…

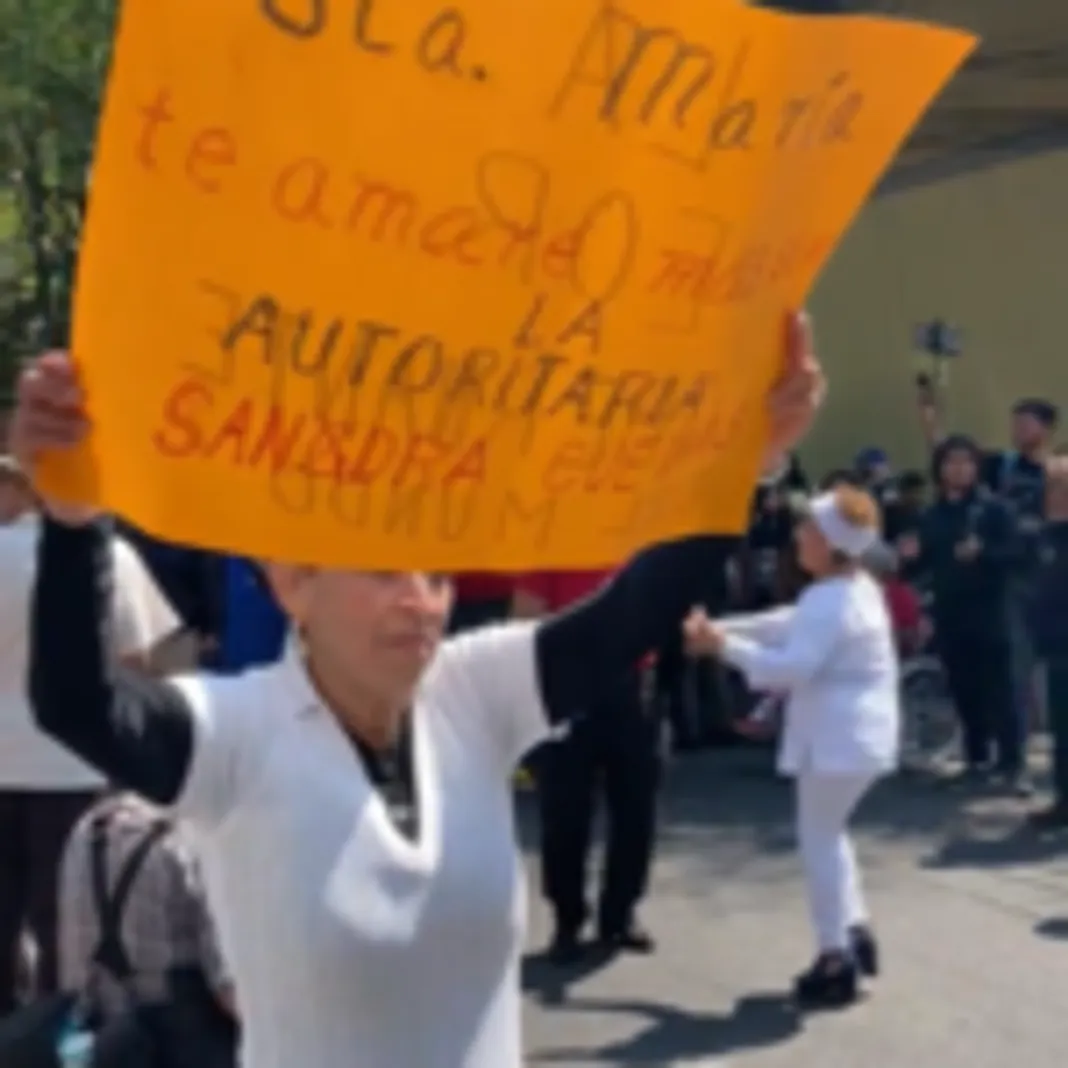

Last February, the right-wing borough president, Sandra Cuevas, who’s now running for mayor, ordered Sonidero Sincelejo and the dancers out of the park for good and cut off electricity to the park to prevent Sincelejo from playing music. The following Sunday, February 19th, there was a protest. I was there and it was quite peaceful. It was … old people dancing. Cuevas responded by sending in violent goons––paramilitary, narco-adjacent thugs called porros that have been used by the Mexican government to put down strikes, protests, and force evictions for decades. They showed up, punched people, pushed people, threatened people, and stole Sonidero Sincelejo’s equipment and entire record collection. (The same thugs followed protestors out of subsequent protests to intimidate them.)

Sonidero Sincelejo’s name is Joel. When Joel left the military, he began to collect rare records, making pilgrimages to Colombia, Venezuela, and Monterrey. Over 15 years, he built an irreplaceable archive of about 250 vinyls. It cost Joel about $350,000 pesos or about $20,000 dollars to assemble but the cultural asset it represents is invaluable.

On March 17th, a judge ordered Sandra Cuevas to return the equipment and records and guaranteed the Sonidero and dancers their right to the use of public space. Cuevas returned only one piece of equipment, which had been destroyed, and zero records. On March 24th, another judge reversed the decision.

Lawyers are now working pro bono to appeal the case. This process could take many more months and may not be successful. While there is a possibility a judge eventually orders the records returned, it’s likely Cuevas will not return them anyway or return them incomplete or damaged. There is a second legal process playing out about the violence inflicted in shutting down the Feb 19 protest. In response, Cuevas embarked on a smear campaign, falsely claiming there were drugs and alcohol being consumed during the dancing. Still, Joel and his wife continued returning to the park, first DJing with bluetooth speakers, then with repurchased equipment and the dancers kept returning to dance. Cuevas has continued making threats and sending goons to loom around the plaza. But she hasn’t been able to shut it down––yet.

Why on earth would anyone want to get rid of the old people dancing in the park?

Cuevas’ stated reason for wanting the dancing out of the park was that neighbors had complained about the noise. But when journalist and TV host, Carmen Aristegui, challenged her to produce the complaints, she could produce only two, and they were from before her administration was in office. Turns out Sandra Cuevas lives in the fancy condo building on the corner of the plaza. Perhaps she was the neighbor that didn’t like the noise. Maybe it was too loud for her. But it’s more likely that it was too … Mexican.

People really hate Sandra Cuevas, but she did not invent her ideology. In Mexico, it’s called malinchismo, after Cortés’ right-hand woman––his enslaved, trilingual, indigenous translator–– La Malinche. She went down in history as a traitor for facilitating the conquest, so they named the widespread Mexican tendency to hate Mexican things after her. It’s the internalized white supremacy left in the wake of colonialism. Cuevas represents Mexico’s right wing, which mostly represents its ascendant upper middle class. This class tends to idolize all things North American––there’s a department store here called Suburbia––and view all things natively Mexican as lesser. For aspirational Mexican people, becoming part of global culture dictated by the commercial culture of the United States is a status symbol; it’s progress.

Two years ago Cuevas ordered all street food stand owners in her borough to paint over their beautiful hand-painted signs called rotulos and replace them with her administration’s logo. The colorful signs, painted in playful, ornate styles that have been passed down through generations are distinctly Mexican. Cuevas called their erasure “an important measure toward order and discipline.” I think Sandra Cuevas wants the music and dancing out of the park for the same reason she ordered the erasure of the rotulos: she sees it all as profane, grotesque, poor-people stuff.

(On the contrary, the Federal government’s left-wing and equally fascist but more populist party, Morena, embraces popular culture. Where Sandra Cuevas wears Armani Exchange, Claudia Sheinbaum, the city’s Mayor and Morena’s presidential candidate, often wears traditional embroidered tops. That’s why the Federal government has put institutional support into the resurgence of cumbia.)

Public space and popular culture are anti-fascist

But there’s another, darker layer: Fascists love destroying culture and controlling public space. They have done so throughout history. Sandra Cuevas is definitely a fascist. Besides her use of goons to put down protests, she was also suspended from office last year for multiple counts of corruption and abuse of power after she tried to sell a public building and also kidnapped a pair of police officers and had them beaten mercilessly for not following orders to remove some street vendors from a plaza. After her suspension, she refused to step down, saying they’d have to kill her to get her out of office. So it’s on brand that Cuevas would have it out for popular culture and use of public space.

I grew up in an over-policed city where parks closed at 8pm and you’d get a ticket for staying any later. In 2007, the City of Chicago planned an all-night street festival called Looptopia downtown and many more people showed up than expected. I remember being deliriously happy, running fast figure eights around The Bean as part of a chain of maybe fifty-something strangers holding hands and chanting, “F**k New York! F**k New York!” This now seems like a funny encapsulation of that giant chip Chicagoans have on their collective shoulder. But also, we were all laughing so hard together, howling, falling down and picking each other up, people of lots of different ages, and it was perfect until the cops came and shut us down. Looptopia was supposed to go til dawn, but around 2am, the City decided it was out of hand, and sent hoards of bike cops to round people up and close the entire downtown. “City’s closed, go home!” It did not phase me.

I learned the concept of the Right to the City as an urban studies major in college but I did not feel it in my body until one morning in 2016 when I watched the sun rise over Carnival in Rio de Janeiro. Thousands of mostly naked people dancing in the streets with no fear whatsoever that any authority would intervene. I thought, “I can’t believe this is allowed.” And then I was struck by a follow up question: allowed by who? Why would anyone intervene?

The streets belong to the people of the city, so of course they could dance down them. They had a right to use their space however they wanted, and what they wanted was to celebrate together. I thought about Looptopia and how what we’d all been high on without realizing it was that––a rare chance to feel collective ownership of our park and to celebrate our beautiful city as A People. I cried. The Right to the City, the free use of public space––to protest or to celebrate (so often one in the same, just look at the history of the suppression of Samba and Carnival)––has felt nothing short of sacred to me since.

This is why it’s important that Sincelejo rebuilds his record collection and brings that music back to the park and the people every week until forever. It’s why preserving a cultural visual language like rotulos isn’t just a matter of maintaining a cute aesthetic but of cultural identity itself––of the social cohesion necessary for the preservation of collective rights in the face of fascism. Popular culture and public space bring people together. They enable collectivity through joy and proximity and provide arenas for protest and revolution.

These days Rich Tech Dudes talk about rockets and AI and “human achievement” and “human potential.” But the single greatest human achievement I can think of is to endure an entire life in this batshit unequal world, and to reach the end of it and to be able to be a fountain of joy for your whole community. The Rich Tech Dudes are lost. The old people dancing in the park have already found peak humanity. And it’s free! All we have to do is make sure they keep dancing.

Zoe Mendelson is a writer, researcher, and information designer. She is the co-founder and editor of the Webby-winning, bi-lingual, inclusive, illustrated encyclopedia Pussypedia.net, author of the bestselling book Pussypedia: A Comprehensive Guide and of the Substack, How to Have Fun in the Apocalypse. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @youngzokeziah or see more of her projects at youngzo.com.

Zoe Mendelson is a writer, researcher, and information designer. She is the co-founder and editor of the Webby-winning, bi-lingual, inclusive, illustrated encyclopedia Pussypedia.net, author of the bestselling book Pussypedia: A Comprehensive Guide and of the Substack, How to Have Fun in the Apocalypse. You can find her on Instagram and Twitter at @youngzokeziah or see more of her projects at youngzo.com.