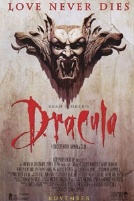

Francis Ford Coppola insisted on calling his vampire movie Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The idea was that this would be the “real” Dracula movie, a movie that harkened back not only to old time fright fests but also dug down deep under the psycho-sexual Gothic horror of Bram Stoker’s original vision. Naturally Coppola missed the mark – but he did something much, much more interesting: he let go of his nostalgia and fell in love with movies all over again.

Francis Ford Coppola insisted on calling his vampire movie Bram Stoker’s Dracula. The idea was that this would be the “real” Dracula movie, a movie that harkened back not only to old time fright fests but also dug down deep under the psycho-sexual Gothic horror of Bram Stoker’s original vision. Naturally Coppola missed the mark – but he did something much, much more interesting: he let go of his nostalgia and fell in love with movies all over again.

Dracula doesn’t look like or feel like any other Coppola movie. Only the production design of One from the Heart gives a hint of the sheer visual exuberance displayed in Dracula. The great failing of One from the Heart, of course, is that the story didn’t match the outrageously beautiful design, leaving a kind of emotional gap from which the film never recovers. That problem is solved in Dracula because the story and theme are so charged. Coppola uses the production design to release all of the sexual anxiety and repressed violent rage Bram Stoker embedded in his story about the shadowy side of Victorian society. To put it another way, Coppola does what great filmmakers do: he brings out theme and emotional subtext through a clear vision, but in the case of Dracula, he turns it up to eleven.

Because Coppola is a genuinely great filmmaker, he has always brought out theme and subtext through production design, but over time he’d developed a relatively repressed style. In the Godfather movies the emotion came from subtext and carefully wrought production design, color palates and lighting. This approach built up to through the period perfection of the Godfather movies through to the psychedelic nightmare of Apocalypse Now. But even Apocalypse Now, on a moment to moment level, was fairly reserved. Dracula loses all reserve. I believe Coppola has always wanted to really let loose with visuals – that’s why he kept trying to make a musical. Musicals are all about emotion breaking through naturalism with song. Dracula does that with a production design that lets go of naturalism all together and permits Coppola an exuberance that frees him from the nostalgia that pulled at him for over a decade.

Even Coppola’s approach to casting Dracula can be seen to move away from naturalism. He moves from the method geniuses of the 70s and to the comic expressiveness of Richard E. Grant, Cary Elwes and a wonderful turn by Tom Waits as Renfield. While Coppola may have been blind to his daughter’s poor performance in The Godfather Part 3, I’m convinced that he had no such delusions when he cast Keanu Reeves as Jonathan Harker. In the first quarter of the movie, Bill, I mean Ted, I mean Jonathan Harker, fumbles about in Dracula’s castle, holding forth with the worst English accent ever mixed. Yeah, it’s absurd, but it’s an absurdity that fits with the almost ludicrous approach Coppola takes to the film. Coppola follows that through by bringing in two of the most over the top film actors of our time in Anthony Hopkins and my personal favorite, Gary Oldman.

I’ll say it right now: Gary Oldman is my favorite living screen actor. He can do anything. Anything. There’s a reason that he has almost always played historical figures or period characters: he has the astonishing ability to be believable no matter how over the top he gets. He can embody anything. In his career he’s played Sid Vicious, Lee Harvey Oswald, Joe Orton, Beethoven, Pontius Pilate, Sirius Black and Jim Gordon, to name just a few. His spirit is somehow indomitable, raw, and craftable, an almost impossible combination. In the first few minutes of Dracula he’s screaming about love, denying God and the church, drinking blood out of a cross, all the while wearing blood-red leather armor – and you believe every minute of it. Gary Oldman is huge in the movie, by turns over the top and understated, enraged and loving, filled with lustful joy and broken by ancient despair, all the while feeling as natural as if he was drinking a cup of coffee.

Another layer to the exuberance of Coppola’s approach to the film is that almost all of the special effects are in-camera tricks. He uses double exposure, rear-projection, time-lapse photography, mirrors and trap-doors; you name it, he does it. And just in case you miss what he’s doing, there’s a sequence in the film where Gary Oldman’s Dracula has gone to an auditorium to check out a “cinematograph.” The cinematograph plays in the background showing the very kind of period in-camera effects Coppola’s emulating throughout the movie, while in the foreground a clever mirror effect shows a white wolf appearing and disappearing as it stalks through the auditorium.

Another layer to the exuberance of Coppola’s approach to the film is that almost all of the special effects are in-camera tricks. He uses double exposure, rear-projection, time-lapse photography, mirrors and trap-doors; you name it, he does it. And just in case you miss what he’s doing, there’s a sequence in the film where Gary Oldman’s Dracula has gone to an auditorium to check out a “cinematograph.” The cinematograph plays in the background showing the very kind of period in-camera effects Coppola’s emulating throughout the movie, while in the foreground a clever mirror effect shows a white wolf appearing and disappearing as it stalks through the auditorium.

For the first time since You’re A Big Boy Now, it feels like Francis Ford Coppola is having fun making a movie. Even with its blood, psychosexual violence and heavy-handed love story, there’s something lovingly filmic about Dracula. I get the sensation that Coppola’s done looking backwards at his life and career and the good old days, and ready to get into the craft of filmmaking up to his elbows.