Happy Endings is hanging by a thread at ABC. Heroes has been canceled since 2010. Pushing Daises has been, well, pushing up daisies since it went kaput almost four years ago. But fans needn’t worry. The word “canceled” simply doesn’t hold that much weight these days. Any defunct show can find new life on another network like Cougar Town did on TBS when ABC tried to kill it, or change everything about itself to stay afloat like The Killing on AMC, or raise enough money on Kickstarter to make a movie to tie up loose ends like Veronica Mars. In fact, in the wake of Mars’ revival, Pushing Daisies creator Bryan Fuller tossed around the idea of a Kickstarter for his baby and more recently, MSN and XBox are eying ways to bring Heroes back to life.

As it turns out, the afterlife is a fertile place for a fallen TV series. And while fans may be rejoicing, we’re all losing out in the long run.

It’s something that’s been a trickling process for years, and it’s just now reaching a head. FX’s Glenn Close-starrer Damages made the switch to what was then the new frontier on DirecTV when it was no longer lucritive for FX, and NBC sentenced the final season of Friday Night Lights to the same fate. Now, we find budding original content providers like TBS and Netflix picking up network scraps like Cougar Town and Arrested Development, hoping for enough success to build future content upon. And while those scraps may have been great and have the potential to be great upon resurrection, they were still scraps. Remnants of television’s circle of life. Things that tried and failed. And this new wave of reviving the dead is disrupting a very important balance.

Writing, pitching, creating, and producing a brand new television show is a terrifying, tireless effort. Networks see thousands of pitches before they even give out their handfuls of pilot orders – typically about 15 or 20. Once the pilot orders are fulfilled, maybe 10 become series, depending on the networks’ needs. And after these series premiere, at least a third will be canceled after only a few episodes. Clearly, there’s months of work (and mountains of money) poured into creating shows that the networks think (hope and pray) that audiences will latch onto. Why would a fledgling original content provider or cable network go through all of that legwork, when some canceled cult series is just sitting there, waiting to be revivied and loved by its hungry, saddened fans?

It’s an opportunity too good to pass up. Yes, TBS and Netflix are coupling their revivals with original content like Men at Work on the comedy-skewing cable channel and House of Cards and Hemlock Grove on the streaming site, lending credibility to their content slate, but they’re also leaning heavily on the security of the revived contents’ built-in audiences. That’s not so bad, right?

Well, it’s not so bad at first. But one trend inevitably begets others, and over at AMC, we’re seeing the results of the trend in the form of a third season of The Killing, the show the Internet loved to hate. Rather than dumping the series and braving a brand new scripted program that could be the network’s next Walking Dead, Mad Men, or Breaking Bad, we’re looking down the barrell of a show we’re not sure we want. True, it could work and it very well might for AMC, but the track record of the rebranded series is generally grim.

If we hobble over to NBC, where the charming series Up All Night was retooled in the hopes of broadening its audience, we find the now demolished remnants of a series that had it almost right only to lose it all by trying to please everyone. Community was allowed to keep going with its meager cultish ratings, even after creator Dan Harmon was kicked out of the roost, but that series has become a deeply saddening shell of itself. Wouldn’t we rather be exploring new possibilities, even if those possibilities turn out to be turkeys like Whitney or even CBS’ canceled Partners, as long as there’s some promise of finding something worthwhile? Wouldn’t we rather reminsce about a series that we loved more than our own siblings than watch it go down in a whirl of flames and mangled parts?

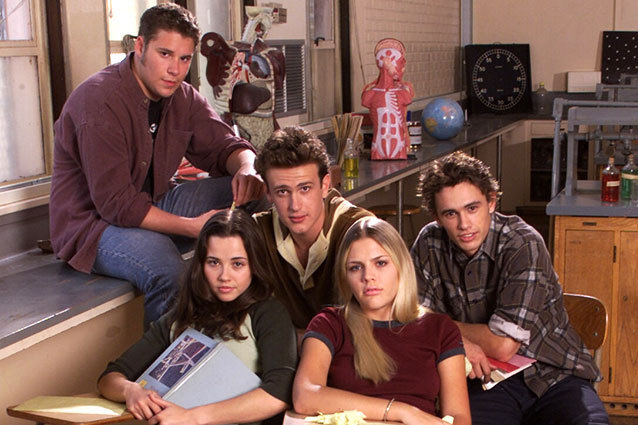

Take Freaks and Geeks, for example. Its single, pristine season which ends with Lindsey Weir’s optimistic journey of self-discovery is heralded as one of the best seasons of television ever. Yet, when it aired, almost no one was watching it. Now it’s a legend, untainted by the hand of network notes meant to drive up viewership and simplify the beauty of the series in its original form. Freaks and Geeks was gone far too soon, but now, it will remain perfect for the rest of time. Its fans will remain fans forever, because no cheap resurgence will mar the perfect memory of the show.

And the more our current slate of canceled shows are brought back in various zombie forms, the more fans will expect some way to continue their symbiotic relationship with their favorite series, rather than going through the normal withdrawal, recovery, and discovery of new material process. The Veronica Mars movie kickstarter is a slap in the face of an example of that: give the fans an opportunity to put their weight behind a project, and they will make it happen. Nearly six million dollars (or $5.7 million, to be exact) doesn’t lie. But it’s like that desire to see more of the happy couple at the end of a romantic movie: if we drag this out, is there the potential of witnessing the ugliness and the cracks that come with too much prolonged exposure? Isn’t it possible to end on an unanswered question and let the moment where our imaginations run wild be the answer in and of itself?

It is possible to end a TV show “before its time,” however abruptly, and still do it justice. It worked for Freaks and Geeks and Arrested Development, and it worked for Veronica Mars, even with that cliffhanger. As excited as I am for movie about the teen sleuth all grown up, it was actually a fitting end to the series to leave Veronica in a puddle of uncertainty. She leaves her troublesome on-again-off-again boyfriend, her father’s fate as Sheriff hangs in the balance, and everything is uncertain. In a way, ending the series with any sense of closure wouldn’t be true to Veronica’s character. Her life is built on tumult, it’s only fair that her TV journey ends that way too, just as Lindsey Weir needed to go off on her wild Grateful Dead tour and Michael and George Michael has to escape their terrible family members on a ludicrous yacht.

And let’s not forget, that while we all mourned the loss of shows like Freaks and Geeks, Veronica Mars, and the soon-to-be-revived Arrested Development, the conclusions of those series allowed the actors, showrunners, creators, and writers to muster up more creative juices and create other projects with potential. Freaks and Geeks creator Judd Apatow took his “failure” on the NBC series (and Undeclared, for that matter) and turned it into creative fuel for his formidable empire of comedy films, starring many of the actors who started on Freaks and Geeks. When Rob Thomas was no longer able to tell stories about Veronica, the teenage sleuth, he moved on to telling hilarious, adeptly crafted (albeit, equally cult-worthy) stories about cater waiters on Party Down, which became so beloved it’s got its own slew of reunion/revival rumors. When Arrested Development went under, many of its stars built successful careers from their small screen success: Jason Bateman became the beloved everyman in big budget comedies, Michael Cera makes millions being awkward, and Will Arnett may not be able to hold a series, but he’s become a beloved comedic actor throughout the industry. Not everything these folks have done is a crowning acheivement, but out of their faltering series came more creativity.

Without these sudden steps back, many of these folks might have lived out their acting/writing/producing days on these shows, risking being branded one-trick ponies before they’d even streched their legs. Instead, they’re people who reached out for something great and didn’t quite grasp it. They are people who deserve a second shot, and they’re people with the fire to make that happen. Generally, I try to avoid quoting old white guys to make a point, but in this case, Thomas Edison really gets it: He said, “If I find 10,000 ways something won’t work, I haven’t failed. I am not discouraged, because every wrong attempt discarded is another step forward.”

That sentiment is the fruit of the creative process. When something isn’t working, whether that’s because of the content itself or the mechanisms that produce and promote the content, it’s an opportunity to stop, reassess, and figure out a way to make it better. In the case of television, it’s not always that the content, jokes, and story lines are bad; it’s that they’re not clicking with the folks they need to click with. And while TV networks are getting better, bit by bit, at giving series more time to breathe and develop before they’re given the axe, we have to, in turn, give them the opportunity to give us something new. We need to learn to leave our comfortable bubbles and let go of the shows that leave us, because that’s when we’re free to discover the next big thing.

Think back to the moment at which you first fell in love with your favorite canceled series. Think of the bond formed with each character. The sudden feeling that you belonged in that show’s setting. The urge to call it home. That feeling is magical, wonderful, and, when it’s really good, it’s almost transcendant. Why settle for the reheated leftovers of something you once adored, when you can create that bond with something you may love even more?

Follow Kelsea on Twitter @KelseaStahler

More:

Study: Women on TV Are Murdered More Violently Than Men

‘Veronica Mars’: Jessica Chastain and 13 Other Surprising Guest Stars

Nine People You Didn’t Know Were on ‘Arrested Development’

From Our Partners Stars Pose Naked for ‘Allure’ (Celebuzz)

Stars Pose Naked for ‘Allure’ (Celebuzz) Which Game of Thrones Actor Looks Least Like His Character? (Vulture)

Which Game of Thrones Actor Looks Least Like His Character? (Vulture)