Every awards season, Shakespeare in Love manages to pop up in conversation as the controversial Best Picture pick of 1998, besting Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan and solidifying Harvey Weinstein as the kind of Oscar races. But you know what people often forget amongst all the hubbub? What a damn fine movie it is.

Every awards season, Shakespeare in Love manages to pop up in conversation as the controversial Best Picture pick of 1998, besting Spielberg’s Saving Private Ryan and solidifying Harvey Weinstein as the kind of Oscar races. But you know what people often forget amongst all the hubbub? What a damn fine movie it is.

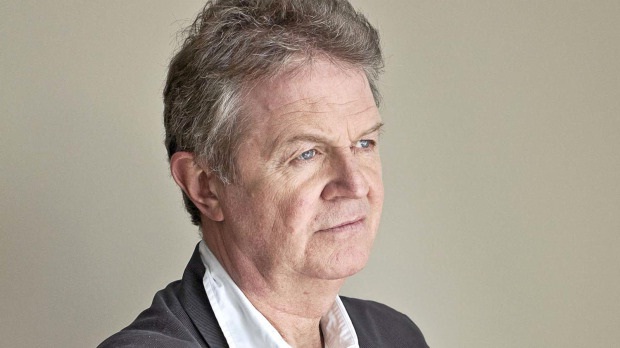

Shakespeare in Love hits Blu-ray just in time for the Academy Award nominations, and I had a chance to sit down with director John Madden (2011’s The Debt and the upcoming The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel) to discuss the making of the film, what going through an awards campaign actually is like and if he would have preferred Shakespeare in Love losing the Oscar. Plus some Jim Henson talk, for good measure.

I’m looking over Shakespeare in Love—thirteen, almost fourteen years ago?

John Madden: Yeah. 1998 we made it. So yeah. That’s fourteen years, isn’t it? Unbelievable.

Right off the bat, is it a movie that you still think about today? Something that you learned, or changed the way you worked? What is your memory of Shakespeare in Love?

JM: Well, it’s kind of all fantastic, really. In a sense that as soon as you finish something you forget the pain and remember the pleasure. [Laughs] It’s like childbirth, apparently. I think it was an incredibly exhilarating film to work on. Incredibly challenging. There wasn’t much of a safety net with it. So, I think it has taught me, if it has taught me anything, it’s not to be worried about that. It’s taught me the incredibly importance of a script…as if one didn’t know that. What I mean by that is, pushing the script as hard as you can. Interrogating the script as vigorously as you can before you start, so you know, essentially, the film that you’re making before you start making it. It’s taught me, so everlastingly, that you haven’t a bloody clue what’s going to work and what’s not going to work in the end! [Laughs] In this sense, I mean, you’ll make a film that you like if you do all the things that I’ve spoken about before. But whether anybody else likes it is something you can’t predict.

But that almost doesn’t matter. As long as you’re making the film that you want.

JM: That’s…right. But it certainly helps if other people like it. [Laughs]

It’s always nice.

JM: But it should never be the objective.

I know that the film passed through several hands on its way to being created. It started with other people working on it, and then it ended up on your plate. How did it end up there? How did, when you came on—talking about ‘rigorously chewing apart a script and making it perfect before you actually make it’—how did it change when you came on board?

JM: Well, I can answer that pretty quickly: I’m not sure that I was aware of the project in its first manifestation at the time. I certainly became aware of it. Famously, it was a script that grew from an idea, or a musing of Marc Norman’s son, who was studying Shakespeare, and said, ‘I wonder how Shakespeare wrote Romeo and Juliet.’ His father, who was a writer—obviously, always on the lookout for ideas—thought, ‘That’s interesting.’ He wrote the first draft—actually, probably before he wrote the first draft, he approached a neighbor of his in Rustic Canyon in Los Angeles, Ed Zwick, and said, ‘What about this?’ And got a commission from Universal, where Ed Zwick had a relationship at the time. That produced a script, some ideas of which are still part of the film. And certainly the basic idea is, [which] was there in Marc’s script.

But Tom Stoppard at that time also had a relationship with Universal to undertake script doctoring or rewriting. And one of the first projects that he elected—with, obviously, the connection, given Rosencrantz and Guildenstern, and given his general level of scholarship about Shakespeare, and so forth. And it didn’t get off the ground—although it got off the ground enough for them to start building sets, and to have cast a great deal of it. But not crucially cast Will. Famously, Julia Roberts was going to play the part that Gwyneth Paltrow eventually played. The film then ran aground I think, because, Julia Roberts lost her nerve with it…well, not lost her nerve. She didn’t have anybody to play opposite. But I think then Universal were relieved to some degree. It was put on the shelf and put into turnaround, and attempts to revive it came to nothing. Until about five years later, when Harvey Weinstein became aware of the script and bought it from Universal with a big price tag on it. Which related to its development costs, but most particularly the money that was spent getting the first production up and running. And they had started to build part of the set up in London.

And did the script change when you came on?

JM: No. So then, Harvey bought that script. I’m sure that he—well, I know that he went to a number of directors with it. I was certainly not the first. This was before, well before it came to me. But Harvey considered it a very precious piece. We had just reconnected. I made a film that he had distributed before called Ethan Frome. I knew him from those days. The Liam Neeson, Joan Allen, Patricia Arquette film in the early ‘90s. Then I made another film he nearly bought. And then he bought [Her Majesty,] Mrs. Brown, the film I made before Shakespeare in Love. And he gave me the script to read at that point. In his very instinctive way. He thought that was a good connection. And I read it. I read what I thought was Tom’s script. It actually turned out not to be Tom’s script. Or at least, maybe it was Tom’s script, but in a very Shakespeare in Love sort of way. It had been doctored by somebody else. It had been polished by somebody else, which we only discovered when I started to work on the script with Tom, and he realized that the script was not his work entirely.

I think it’s true to say, to answer—I’m sorry, that was a bit delayed—he got the script to a certain point. It was like a first draft, maybe even a second draft. But part of it had not really been completely landed. Most particularly, I suppose, the last act of it. And there were a bunch of things that we started to talk about. The Marlowe character—the part that Rupert Everett played—came into the script in a proper way at that point. I think it’s probably fair to say that Tom had originally envisaged the movie as a Zucker Brothers farce. A sort of willfully irreverent farce with outrageous jokes, and so farth. And I suppose it’s fair to say that I felt it should have all of that, but also the flavor of a mature, Shakespearean comedy. In other words, that the romantic core of the piece was an important part of the narrative as well. And so, the script began to move in that direction. But then, particularly, the biggest development of it, was in the last act, I suppose, of the film. The performance of the play. The relationship at the core of it, and so on.

It’s funny that the Blu-ray is coming out right now, in the thick of awards talk and buzz for this year. I’m curious about what your own experience was like going through the awards season with this movie. I know that Harvey’s a big guy in that scene, and in helping to push these movies, and get them in the eyes of many people. What was your experience like running with this movie during that season?

JM: It happened fast, to be honest with you. I’m not saying it’s hard to remember. It’s not hard to remember at all. It’s very vivid. [Laughs] One of the things that happened was that we kind of came into the front of the pack for Miramax, which always had a bunch of movies at that time that might potentially have been awards contenders. I think that one movie they thought might be, turned out not to be. And we moved into, sort of, pole position. Which helped us a little bit, because I think that he might have pushed harder for certain changes to have happened in the film, which I was able to resist, because I didn’t think they were right and because there wasn’t time to do them if the film was going to be ready. We literally had a press screening with an Anser printer. I remember, we hadn’t even done the print of the film. I think it was like three days after we had completed the sound mix. And at that point, we discovered that the film had an almost unanimous critical reaction, which we weren’t prepared for.

We’d been through the usual process with a film of research screenings and so forth. And I knew, from my days in theater and being in a room with an audience watching a film, I knew the film was connecting. Of course, the glorious thing with a comedy is that it’s measurable and you can hear it. But in terms of in scores, they weren’t particularly startling. So we didn’t know, and that is, I think, because—I don’t know—jaded New York audiences want to offer their views on everything. Who knows what it was! But in fact, the film suddenly took off like a rocket. There’s one blessing about that film: it’s so rich, it’s such an incredibly audacious and brilliant script. And quite rich in terms of what it offers you. The sort of range of emotions that it offers you. And being about Shakespeare, and borrowing from Shakespeare—it has a sort of density, and a level of mystery to it. Even beyond all of that. It was the most wonderful film to talk about, just because there was a lot in it. I remember that very clearly. I was giving wall to wall interviews for days and days and days.

I can imagine.

JM: And I haven’t done that on this film for—when did we just decide it was? Fourteen years, or whatever? It was pretty intoxicating. And also, we were an underdog. We had just come out of nowhere. None of us working on it expected it to be that or to do that. We just thought the people who are in the world that we’re in would enjoy this. It’s a love letter to the theater, at least in part. And most of us who worked on that film, at least in the acting department and in my department, had spent a very large part of their lives doing exactly that. So, we thought those people would get it. We had no idea it would translate. We were fighting off title changes right to the end. Mostly because they thought we’d better get the word ‘Shakespeare’ out of the title, or no one would ever come.

People are so scared of it. This might be kind of a strange question, but do you ever wish the movie hadn’t won Best Picture that year? Or do you think it really did help the movie to kind of win that top dog award?

JM: I’ve never stopped thinking that I wish it hadn’t won from the moment it did. [Laughs] No! I can’t say that I have! Not really. I imagine that that question is directed at—

It kind of gets swept up in a lot of back and forth of, ‘What should win?’ I think every Best Picture does.

JM: Yeah. And there are always going to be those that say Saving Private Ryan should have won. Or even others that weren’t nominated. Of course, that goes with the territory. But no. I haven’t thought that. Obviously, it is a game changer, professionally speaking, because—not in the obvious ways, in the doors it opens—simply because it becomes…you realize, wherever you go in the world, people know that film, as they do with any film that has won that particular prize. It gives it an international currency. There’s something liberating about that. But does it become a talisman around your neck that you can’t get rid of? Yes. But we should all be lucky enough to have that. I’m not complaining about that. I think, the shorter answer, really, is that it shouldn’t, in the end, be about prizes. It should be just about—there are plenty of fantastic films that are out there that endure. Seminal pieces that didn’t win that prize. Obviously, the list is endless. And I’m not saying it confers a classic status on the film in any way, but it ensures it a kind of longevity. Not necessarily because of my part in it, but certainly because of the script and the subject matter. I think it deserves a long life. It’s a properly mature, brilliant piece, I think.

I have two kind of random questions. One: did you see the Anonymous film? The Shakespeare film?

JM: I have not. I have it. I’ve got a screener with me. I brought it. It hasn’t been released in the U.K. Or at least if it was, it was released when I wasn’t there. Because I’ve been working over here. And so I chased it around in terms of cinemas. I have a screener and I’m going to watch it in due course. I’ll be fascinated. Of course, it’s made by a Flat Earther so I don’t know that I’m going to be ideologically sympathetic to it. But I’ll be very interested to see it. Because I know they’ve thrown much more—apart from everything else, never mind the contentiousness of its subject matter—they throw much more digital effort in recreating Elizabethan England. So I’ll be interested to see what that looks like at least. We did not have those funds available.

You didn’t have giant green screens in Shakespeare in Love.

JM: No. We did have some green screens…

And just to wrap up, I was looking back at some of the things you have directed in your past. It appears that you directed an episode of one of my favorite TV shows of all time: The Storyteller.

JM: Oh yes! Right!

So you directed the ‘Theseus and the Minotaur.’

JM: Yes. ‘The Mynotaur’. Yes.

An amazing little piece of television, there. I was kind of curious about you working with the Henson Company. I don’t know if Jim [Henson] was actually alive when you did the episode.

JM: He was. But he didn’t…he was really the kind of distant master. Admired from afar. The Henson Company had a presence in the U.K. That operation was run by Lisa, his daughter. But the Creature Workshop was based in the U.K.. As you know, the initial idea of The Storyteller was fairy tales. And they were produced by a friend of mine, called Duncan Kenworthy. The story editor and writer of all of those scripts was Anthony Minghella, another friend of mine. They were very, very successful. And the idea came up, then, to do the Greek myths as the next [season]—Grimm’s fairy tales was the first one, and the Greek myths was the second one. And, so, four were commissioned, of which ‘Theseus and the Minotaur’ was the first. Anthony wrote the script. And all I know was that Jim was very, very, very excited by them. Because those stories are the roots of modern psychology. And it was a world that, at that point, we were relatively unfamiliar with. You know, in film. So it was a pretty amazing experience. They had very, very good budgets. They called upon and could call upon quite sophisticated visual effects for the time. An absolutely amazing production team: Roger Pratt shot it. John Beard designed it. And a terrific cast. It was amazing to do. It was a level of filmmaking for television that was pretty unprecedented at the time. And now, I think, a staple of a lot of schoolrooms, because it has got fantastic educational tools.

I look forward to seeing a Minotaur pop up in one of your future films. I hope.

JM: [Laughs]

What’s next on your plate? I know The Best Exotic Marigold Hotel is coming out sometime this year?

JM: Yes. It’s coming out in April in the U.S., and late February, early March in the U.K. Yeah, that’s the next thing up.

Are you in the middle of shooting anything?

JM: Well, I’m working on a pilot. An American television pilot for Showtime right now, which is why I’m in New York. It’s about the sex researchers Masters and Johnson. The U.S. sex researchers in the ‘50s. Which is a pretty interesting piece.

Are you a producer of the show?

JM: Yes. Well, I’m an executive producer of the show, and I’m directing the pilot. It’s written by Michelle Ashford.